Termite Biology (eastern subterranean termites and Formosan termites)

Basic Biology

Termites are related to cockroaches and are now classified in the same order as cockroaches, Blattodea. (Until recently, termites were placed in a separate order, Isoptera.) Like cockroaches, termites have a gradual life cycle, meaning they have three stages of development: egg, nymph, and adult. Developing termites do not have an inactive pupal or resting stage like bees, butterflies, or other insects that have a complete life cycle.

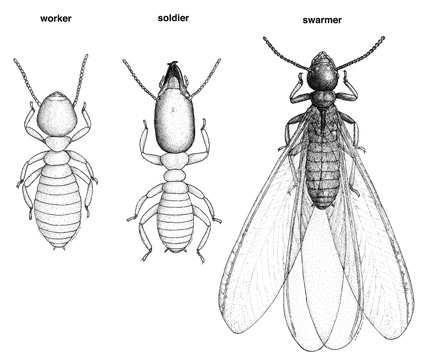

Termites are social insects. This means they live together in colonies in which there are overlapping generations and a division of labor among different castes. Each colony contains three major castes of adult termites: workers, soldiers, and reproductives (Figure 1).

Workers (Figure 2) are by far the most numerous, constituting around 90 to 98 percent of the colony members. Worker termites are sightless (no eyes), completely white (without pigmentation), and are the caste responsible for foraging, building tunnels and caring for the young. Unlike ants, bees, and wasps, in which all workers are female, termite workers may genetically be either male or female, but there is no functional difference as long as they remain as workers.

Soldiers (Figure 3), distinguished by their enlarged, darker colored heads and large, stout mandibles, are the next most numerous caste. Depending on species, anywhere from 2 to 4 percent (eastern subterranean termites) and up to 10% (Formosan termites) of the termites in an established colony will be soldiers. As their name suggests, soldiers are responsible for the defense of the colony and will immediately respond to breeches in tunnel walls or other attacks on the colony (Figure 4).

Reproductives are the colony members responsible for mating and laying eggs, but there are three different types of reproductive termites. Primary reproductives are the queen and king. These are the termites that left their parent colony as swarmers (Figure 5), flew away from the parent colony and paired up to establish the new colony. Unlike ants, bees, and wasps, male reproductive termites, known as kings, assist the female in founding the colony and remain inside the colony with the queen to mate repeatedly over time. Because these are the only termites that leave the protective environment of the colony and are exposed to sunlight, primary reproductives are the only members of the colony that have pigmentation and eyes. Once they have paired up and fallen back to the ground, termite swarmers shed their wings (Figure 6) and attempt to establish a new colony. Primary reproductives can live as long as 10 to 15 years, and queens in well-established colonies can produce thousands of eggs per day.

Well-established colonies may also contain secondary and tertiary reproductives. These are reproductive termites that developed from some of the nymphs or workers inside the colony. (Note that most workers remain workers for their entire life and do not become reproductives or soldiers.) Secondary reproductives develop from nymphs and have wing pads but do not have fully developed wings. Tertiary reproductives develop from workers and do not have wing pads. In a mature, well-established colony the combined egg-laying capacity of the secondary and tertiary reproductives may exceed that of the queen, and an established colony with secondary and tertiary reproductives can continue to survive and thrive if the primary queen dies. If a portion of a termite colony containing secondary or tertiary reproductive becomes cut off from the parent colony for some reason, it may continue to survive and grow as a separate colony. This is how most aerial colonies become established in buildings. If an aboveground portion of a colony contains secondary reproductives and has a constant, aboveground moisture source, it does not need to constantly return to the soil for moisture and can become completely independent of the parent colony.

Colony establishment and growth

Termite colonies begin when a pair of swarmers settles to the ground after the mating flight (Figure 7). The two swarmers find a crevice in the soil, seal themselves in, and mate. The young queen lays her first eggs, which hatch into nymphal workers. These first workers forage on nearby cellulose material, such as decaying bits of wood, mulch, leaves or pine needles. Recent research has shown that fallen pine needles are one of the best food sources for young Formosan termite colonies. As more workers are produced, they expand the nest galleries and forage farther from the colony. New termite colonies grow slowly. After the first year a newly founded colony may contain fewer than 50 termites and there may be only a few hundred after 2 years. It takes about 5 years or longer for a colony to grow large enough that it may be able to invade a building or produce swarmers of its own. The population of a mature colony of Eastern subterranean termites ranges from around 50,000 to several hundred thousand termites. Although unusually large Formosan termite colonies may exceed one million individuals, most colonies are smaller.

An acre of southeastern forest or urban southeastern landscape is inhabited by many different colonies of termites, with as many as 25 colonies per acre being found in one study in North Carolina. In some cases a building may be infested by two or more different colonies of termites, and simultaneous infestations of eastern subterranean termites and Formosan termites are occasionally encountered in Mississippi.

Feeding and foraging behavior

Termites are one of the few animals that are able to utilize cellulose as a food source. Their guts contain an array of special protozoa, other microbes, and enzymes that are able to break down cellulose into nutrients that the termites can utilize. This allows termites to eat wood, which is their primary food source, but they will also feed on other items that contain cellulose, such as books, cardboard, or paper. This explains why termites are often found tunneling through the cardboard covering of sheetrock walls and why homeowners occasionally find termites feeding in rows of books on a bookshelf or in boxes of stored papers. It also explains why even buildings that are built largely of concrete and steel cannot be considered “termite-proof,” and why it is still important to preventively protect such buildings from termites.

Termites prefer some woods over others. Eastern subterranean termites will feed on hardwoods, but they prefer pine and other softwoods, and even in pine lumber will preferentially feed on the soft spring-growth portions of the growth rings, leaving the summer growth intact (Figure 8). Eastern subterranean termites do not attack cypress, but Formosan termites will readily attack cypress, as well as pine and other softwoods and hardwoods. Both species prefer wood that is moist, and the presence of moisture and wood decay fungi makes wood even more susceptible to termites.

Termite workers forage by tunneling through the top 6 to 12 inches of soil in hopes of encountering a piece of wood. There are exceptions, and termites will sometimes tunnel deeper in the soil, but the majority of foraging is in the top few inches. Although they can detect leachates from wood from relatively short distances, termites forage randomly in all directions from the nest site. When a wood source is detected, the workers will recruit other workers to the area to exploit the source and establish feeding tunnels to the source. If the source is large enough and has sufficient moisture, they may eventually establish satellite nest sites, with secondary reproductives, in the area or in the source itself.

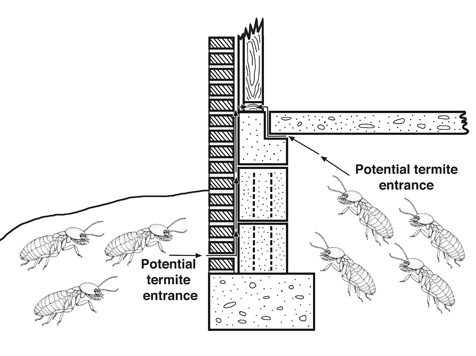

When forced to travel above ground because of rocks or other impenetrable substances, termites will build mud foraging tubes over the hard surface. This is because termites are highly susceptible to desiccation and must maintain high humidity inside their colony, tunnels, and shelter tubes. These shelter tubes also provide protection from predators such as fire ants. When foraging termites encounter concrete or brick building foundations, they often build mud shelter tubes up or over the surface (Figure 9), and this is one way termites are able to invade buildings. Foraging termites are also very adept at tunneling through hidden cracks and crevices to enter buildings (Figure 10), which means that points where termites are entering buildings are often not visible and may be impossible to detect, even by experienced termite technicians.

Dr. Blake Layton, Extension Entomology Specialist

Department of Entomology, Mississippi State University

Phone: 662-325-2960

Email: blake.layton@msstate.edu

Publications

News

Mississippi’s native subterranean termites have started swarming, and these structure-destroying insects will continue to swarm across the state over the next few months.

John Riggins, professor of forest entomology in the Mississippi State University Department of Agricultural Science and Plant Protection, said termites swarm to produce new colonies when the weather warms up, often after a rain.

Termites exist all over Mississippi and will eventually infest and damage any structure that contains wood or other cellulose components unless you properly protect those structures.

Invasive Formosan subterranean termites were first found in the state 40 years ago, and soon, these dangerous pests will swarm and threaten unprotected structures in about one-third of Mississippi’s counties.

Santos Portugal, Mississippi State University Extension Service urban entomologist, said Formosan termites typically swarm in the millions from early May to early June. They have the ability to infest and significantly damage structures much more quickly than native subterranean termites.

Success Stories

A dream of the Mississippi Pest Control Association and the Mississippi State University Extension Service is coming true after more than 20 years, thanks to a generous donation by one of Mississippi’s oldest pest-control companies.