Snakes Alive! How to Identify Hazardous Snakes

Snakes are important members of the natural world. All make a significant contribution to the control of pests such as mice, rats, and insects that can cause property damage or spread diseases. Kingsnakes—so named because they feed on other snakes, including venomous ones—are particularly beneficial to people.

Venomous snakes produce venom for killing prey, for defense, and to aid in digestion. Usually, snakes inject venom into a prey or enemy target with hollow or grooved fangs. Because of their hazard, venomous snakes are not welcome members of human habitat. Their best place is in the wild.

Despite their notorious reputation, snakes are peaceful creatures that do not seek out encounters with much larger humans. They remain motionless or flee to avoid detection. If threatened, a snake often issues a warning by hissing, flattening its head, opening its mouth, or vibrating its tail. A snake generally bites after an “enemy” ignores these warnings or if it is startled into reacting quickly (for example, if you step on it).

It is important to remember that the risk of a venomous snake bite is very low. Most snake bites are the unfortunate consequence of people’s attempts to harass or kill snakes, even snakes that may not have been a threat (for example, snakes encountered in nature rather than in home settings). Follow these steps to reduce the risk of snake bite:

- Clean up debris and remove hiding spots for snakes and their prey from around buildings and yards. See Mississippi State Extension Publication 2277, Reducing Snake Problems Around Homes, for more information on this topic.

- Wear heavy shoes and pants in wooded areas and along waterways or water bodies.

- Look before stepping where snakes are likely to be hiding—along or under logs, rocks, culverts, or other natural or manmade structures.

- Give any snake you encounter plenty of room to leave the area on its own.

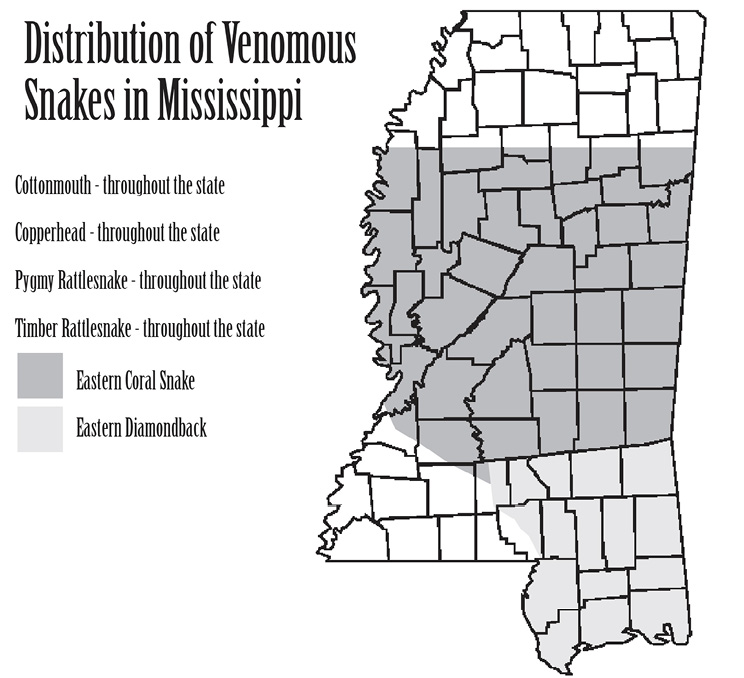

Most venomous snakes in the United States belong to the pit viper group. A pit viper is characterized by several traits: (1) pits or small depressions on the side of its face (used in prey detection); (2) vertical “cat-like” pupils; (3) triangular head, slim neck, and a heavy, flattened body; and (4) a single row of scales on the underside of the tail. Some of these characteristics can be difficult to detect from a safe distance, but the triangular head and slender neck are more recognizable. In Mississippi, the pit viper group includes the copperhead, pigmy rattlesnake, eastern diamondback rattlesnake, timber or canebrake rattlesnake, and cottonmouth or water moccasin. The sixth type of venomous snake in the state, the eastern coral snake, is not a pit viper. Coral snakes are characterized by rounded rather than triangular heads, indistinct necks, round pupils, smooth scales, and hose-shaped bodies.

Mississippi’s Venomous Snakes

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake

The eastern diamondback rattlesnake is the largest venomous snake in North America, averaging 5½ feet in length. The record eastern diamondback was an impressive 8 feet long. As the name implies, the diamondback rattlesnake is characterized by dark diamond shapes edged in light yellow on a lighter brown background. As with other pit vipers, the body tends to be somewhat flattened at the belly, particularly in larger snakes; they do not appear as “hose-shaped” as most nonvenomous snakes. Rattlesnakes add a new button to their rattles every time they shed (several times each year). These buttons can break off over time, so a rattlesnake cannot be aged by the size of the rattle. Habitat loss and indiscriminate killing are contributing to declining numbers of this species.

Timber Rattlesnake

Also known as canebrake rattlesnakes, these snakes are found in a variety of Mississippi habitats, including forests, swamps, and agricultural fields. This species averages 2½ to 5 feet in length and shows the pit viper characteristics of a heavy body, triangular head, narrow neck, and keeled (ridged) scales. A timber rattlesnake can vary from gray to brown, but it is characterized by dark stripes that drape across its back and sides. These markings camouflage the snake in ground vegetation. Similar to other rattlesnakes, the timber rattlesnake shakes its rattle as a warning before striking.

Pygmy Rattlesnake

As the name implies, a pygmy rattlesnake is small, averaging 18 to 20 inches in length. Its thick body has an overall gray to gray-brown appearance marked with rows of dark blotches along the back and sides. Its rattle is small and can be easily broken off, giving some the incorrect impression that this rattlesnake species is silent.

Copperhead

The copperhead was named for the bronze tones on its head. It is not uncommon for snakes to vary in color within a species, and copperheads display this trait. Its heavy body (averaging 20 to 26 inches in length) ranges in color from tan or golden brown to shades of gray. All are marked with darker hourglass patterns that lie across the animal’s upper surface. A young copperhead is easily identifiable by its bright-yellow tail tip.

Cottonmouth

The cottonmouth prefers habitat near fresh water, which contributes to its colloquial name, water moccasin. The average length of this heavy-bodied species is 2 to 4 feet, and its color varies greatly from completely brown or olive to marked with dark bands on a lighter background. The young cottonmouth has a yellow-tipped tail. When threatened, a cottonmouth opens its mouth to expose the cottony white interior for which it is named. It is often confused with species of nonvenomous water snakes, such as the Mississippi Green Water Snake.

Coral Snake

Coral snakes are brightly colored venomous snakes encircled with red, yellow, and black bands. Unlike the other venomous snake species in Mississippi, coral snakes lack the characteristic wide jaws and slender neck of pit vipers. This smaller snake species (average length is 2 to 3 feet) lives in sandy pinewoods. Coral snakes can be confused with nonvenomous scarlet kingsnakes and milk snakes, but a rhyme can help sort out the differences in most cases: “Red touches black, friend of Jack; Red touches yellow, kills a fellow.” The coral snake has red bands that touch yellow bands. Although not all coral snake bites will “kill a fellow,” it can be a life-or-death situation that requires immediate medical attention.

If you are bitten by a snake...

- Get emergency medical help as soon as possible. As much as possible, refrain from moving about quickly.

- Remove all items that may restrict circulation in the affected area. Watches, bracelets, rings, gloves, or shoes may pose a problem as the bite area swells.

- Immobilize the affected area as much as possible. Attempt to keep the bite at or slightly below the level of the heart.

- If the snake is still in the area, do not attempt to kill or catch it. Try to remember what it looks like so you can identify the type of snake from pictures in the emergency room.

- Do not take these actions:

- Place a tourniquet or constricting band above the bite;

- Give the victim anything to eat or drink, particularly alcohol;

- Place the affected area in ice;

- Make any cuts or apply suction to the area;

- Attempt to give antivenom; or

- Administer pain or antianxiety medications.

For help, call the Mississippi Poison Control Center at 1-800-222-1222.

Publication 3529 (POD-9-20)

Revised by Leslie Burger, PhD, Assistant Extension Professor, and Alexander J. Binney, Extension Program Assistant, Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture. From Bronson Strickland, PhD, Extension Professor, and the original information sheet by L. R. Shelton, former Extension wildlife specialist.

Copyright 2020 by Mississippi State University. All rights reserved. This publication may be copied and distributed without alteration for nonprofit educational purposes provided that credit is given to the Mississippi State University Extension Service.

Produced by Agricultural Communications.

Mississippi State University is an equal opportunity institution. Discrimination in university employment, programs, or activities based on race, color, ethnicity, sex, pregnancy, religion, national origin, disability, age, sexual orientation, genetic information, status as a U.S. veteran, or any other status protected by applicable law is prohibited. Questions about equal opportunity programs or compliance should be directed to the Office of Compliance and Integrity, 56 Morgan Avenue, P.O. 6044, Mississippi State, MS 39762, (662) 325-5839.

Extension Service of Mississippi State University, cooperating with U.S. Department of Agriculture. Published in furtherance of Acts of Congress, May 8 and June 30, 1914. GARY B. JACKSON, Director

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.