Protein in Beef Cattle Diets

Feed costs account for a large proportion of cash costs in beef cattle operations. Protein is a critical nutrient in all beef cattle diets. Although protein supplementation is often a high-cost item in beef cattle feeding programs, sometimes protein supplementation is needed to meet the animal’s nutrient requirements.

Signs of protein deficiency include lowered appetite, weight loss, poor growth, depressed reproductive performance, and reduced milk production. Providing adequate protein in beef cattle diets is important for animal health and productivity as well as ranch profitability.

Protein Defined

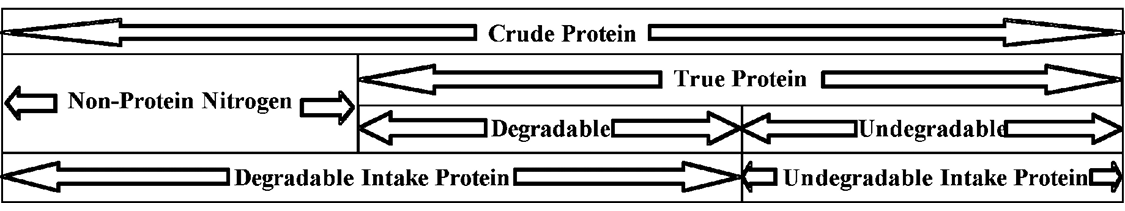

Protein in beef cattle diets is commonly expressed as crude protein. To determine the crude protein content of a forage or feedstuff, first measure the nitrogen content of the feed. Then multiply the nitrogen value by 6.25, because proteins typically contain 16 percent nitrogen (1/.16 = 6.25).

Crude protein is comprised of both true protein and nonprotein nitrogen. Not all nitrogen-containing compounds are true proteins. Urea is an example of a nonprotein nitrogen (NPN) source. Many NPN compounds can supply nitrogen to the rumen microbes that then build microbial protein in the rumen using this nitrogen.

True protein is sometimes called “natural protein.” It is either degradable (can be broken down) or undegradable (cannot be broken down) in the rumen. Ruminally degradable protein (RDP) is broken down in the rumen and is also referred to as degradable intake protein (DIP). Ruminally undegradable protein (RUP) is not broken down in the rumen but is potentially degradable in the small intestine. It is sometimes called undegradable intake protein (UIP) or rumen bypass protein. A minimum amount of DIP is needed in the diet to support microbial growth. Otherwise, the intake and digestibility of the diet will be limited. Crude protein is the sum of UIP and DIP.

Metabolizable protein accounts for rumen degradation of protein. It separates protein requirements into the needs of rumen microorganisms and the needs of the animal. Metabolizable protein is true protein absorbed by the intestine. It is made up of microbial protein and UIP.

Protein Supplies and Cattle Nutrient Requirements

Beef cattle diets in Mississippi are primarily forage based. The protein composition of forages typically varies by forage species, soil nutrients, and forage maturity. Cool-season forages tend to contain higher crude protein levels than warm-season forages. Crude protein concentration also generally decreases with increasing forage maturity and decreasing nitrogen fertilizer rates.

Insufficient protein can be a problem on warm-season grasses receiving inadequate nitrogen fertilization, particularly when forage is allowed to become mature before harvest or when frosted pasture is grazed during winter. Excessive rainfall can also leach nitrogen from the soil and reduce nitrogen levels available for plant protein production and animal consumption.

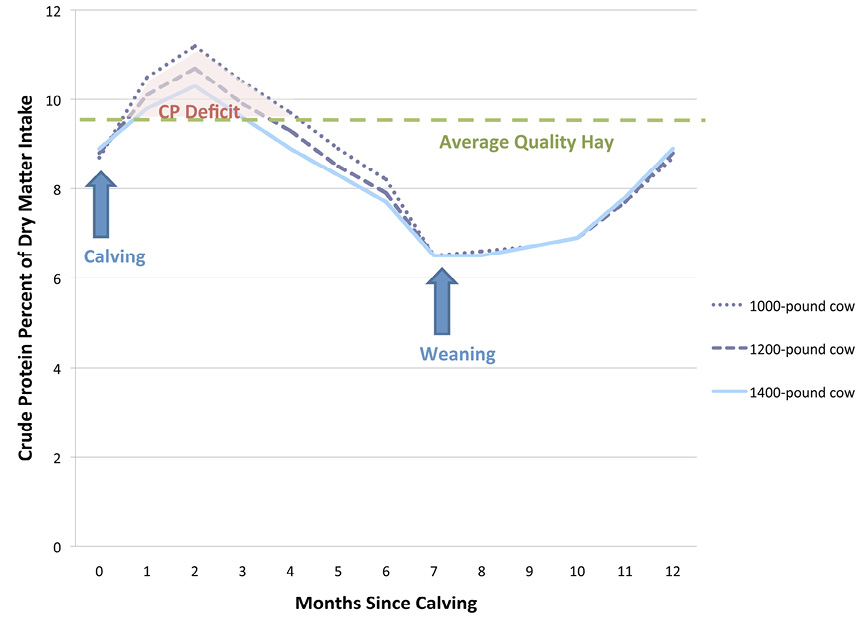

Cattle protein requirements vary with stage of production, size of the animal, and expected performance. During lactation, larger cattle typically require more pounds of crude protein per day than smaller cattle but as a lesser percentage of their total dry matter intake. In other words, lighter cattle require higher-quality feeds and forages at lesser quantities compared with heavier cattle. Cattle requirements for crude protein increase with increasing lactation and rate of gain. Protein is required for milk production and reproductive tract reconditioning after calving.

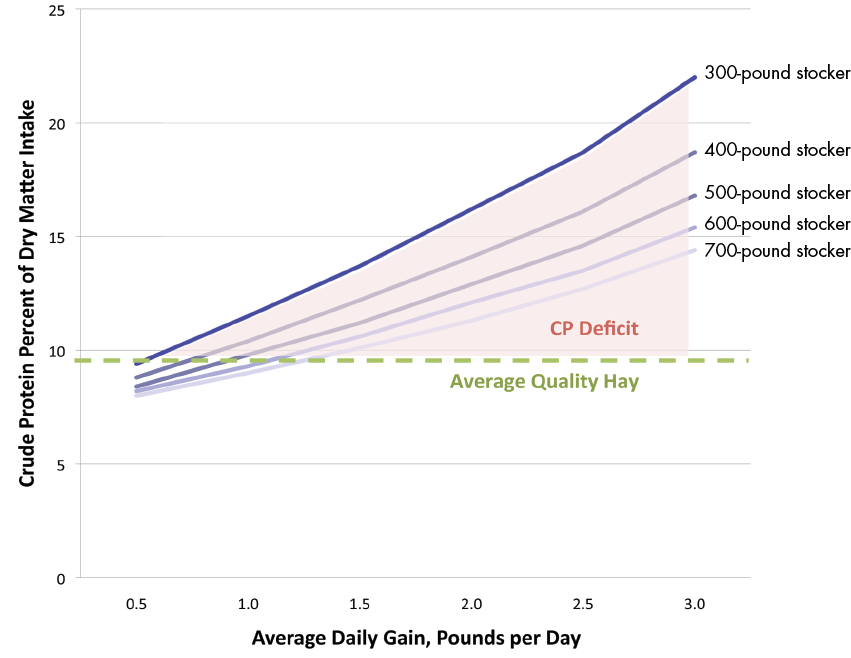

Young, growing cattle, in particular, need relatively high levels of crude protein in their diets to support muscle growth. Creep feeds or forages for nursing calves should contain at least 15 percent crude protein. High-protein creep feeds are best used when forage availability is abundant. Average daily gains in nursing calves tend to increase with increasing crude protein content of creep diets, but the expense of the diet will likely also increase with increasing protein levels.

Additional protein and energy are often required to properly balance diets for growing cattle and lactating beef cows on forage-based diets. This is especially true when low-quality stored forages are the majority of the diet, as is often the case during the winter hay-feeding period after a poor hay production season or with hay produced under low levels of management.

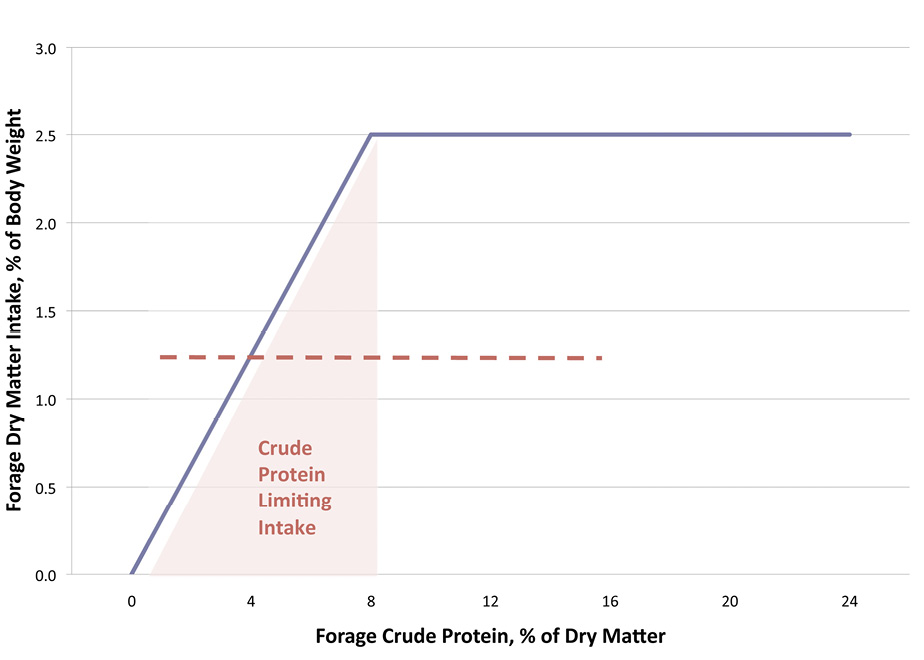

Limiting dry matter intake on poor-quality forages is another concern with regard to the crude protein content of the diet. Generally, forage dry matter intake as a percent of body weight increases until forage crude protein content as a percentage of dry matter decreases below a threshold of about 8 percent. Thus, if a minimum of 8 percent crude protein is not maintained in forage crops, cattle will decrease consumption of these poor-quality forages

When crude protein is below 8 percent, rumen bacteria responsible for digesting forage cannot maintain adequate growth rates. Forage intake and digestibility will then decrease. Crude protein supplements are appropriate under these conditions to stimulate forage intake. Forages with adequate levels of crude protein will not require protein supplementation to improve intake but may need crude protein supplementation if cattle nutrient requirements for crude protein are not being met by the forage alone. If the forage supplies at least 8 percent crude protein, then forage intake will likely decrease with the addition of protein supplements fed at a rate of 0.3 percent of body weight or more as a substitution effect takes place. Forage quality testing is an invaluable tool for determining stored forage crude protein concentrations in advance of feeding.

|

Forage |

Stage of Maturity |

Crude Protein, % of dry matter1 |

|---|---|---|

|

Alfalfa |

Bud |

22–26 |

|

Early flower |

18–22 |

|

|

Mid bloom |

14–18 |

|

|

Full bloom |

9–13 |

|

|

Corn silage |

Well eared |

7–9 |

|

Fair to poorly eared |

7–9 |

|

|

Tall fescue, orchardgrass |

Vegetative – boot |

12–16 |

|

Boot – heat |

8–12 |

|

|

Annual ryegrass |

Vegetative – boot |

12–16 |

|

Boot – heat |

8–12 |

|

|

Bermudagrass |

4 week old |

10–12 |

|

8 week old |

6–8 |

|

|

Pearl millet, sorghum-sudangrass |

8–12 |

|

|

Red clover |

Early flower |

14–16 |

|

Late flower |

12–14 |

|

|

Annual lespedeza |

12–16 |

1Forages containing >19% crude protein are considered prime quality, while forages <8% crude protein are classified in the lowest quality standard.

Source: Adapted from Ball et al., 2007. Southern Forages. 4th edition.

Protein Supplements

Protein supplements are available in many forms. High-quality forages, commodity co-product feedstuffs, range cubes, protein blocks, and liquid supplements are some examples. Consider cost per unit of protein and convenience of various protein supplements. Base purchasing decisions on the cost per pound of protein instead of the price per pound of supplement. Product labels indicate the protein percentage and how much protein is in the form of nonprotein nitrogen. Convenience products often contain NPN and are generally higher in price per unit of protein. Be sure to read all feed tags, checking for NPN content in range cubes, protein blocks, and liquid supplements, in particular.

The molasses content of liquid supplements is usually not high enough for proper NPN use when supplementing low-quality forages. Similarly, while liquid supplements and protein blocks often meet protein requirements, these supplements rarely provide adequate amounts of supplemental energy for lactating cattle fed hay. Mississippi forage test results indicate that energy is the limiting nutrient in meeting beef cattle requirements more often than protein. Monitor body condition and adjust energy supplementation as needed.

Consider using high-quality forages such as vegetative legumes and cool-season forages to supply protein in beef cattle diets when possible. Use commodity-based co-product feedstuffs to supplement forage-based diets for stocker calves and lactating cows for the best supplement values if the operation is set up to store and handle these feeds. Examples of feedstuffs (and their typical protein concentrations on a dry matter basis) that can serve as effective protein supplements include soybean meal (48%), cottonseed meal (41%), whole cottonseed (24%), corn gluten feed (24%), dried distillers grains (27%), and brewers grains (26%). Dried distillers grains are considered relatively high in UIP.

Nonprotein Nitrogen

Urea is a form of NPN that can be fed to beef cattle. Producers may consider its use due to economics. However, use caution when including urea in beef cattle diets. It can be toxic if improperly used. Urea is quickly converted to ammonia upon entering the rumen. This ammonia can either produce proteins (from bacteria and a readily available energy source) or enter the bloodstream. If energy sources are limited in the rumen or if too much urea is consumed, then large amounts of urea can enter the circulatory system. When the amount of urea entering the bloodstream exceeds the capacity of the liver to remove it, cattle can suffer from ammonia toxicity or urea poisoning—with death resulting in less than 30 minutes.

Preventing urea toxicity is always better than having to treat it. Instances of urea poisoning are commonly caused by improper weighing or poor mixing of urea into cattle feeds. Overconsumption of liquid or solid molasses-based supplements containing urea by hungry cattle can also lead to urea toxicity. Feed range cubes that contain NPN on a daily basis rather than feeding larger amounts a few times a week. Fill cattle up on hay before placing liquid supplements or “lick tanks” containing urea in pastures. Once cattle are acclimated and start consuming liquid supplements, do not let them run dry. If dry lick tanks are suddenly filled, cattle may overconsume NPN.

Never feed raw whole soybeans and urea together. Soybeans contain an enzyme called urease that breaks down urea into ammonia. This combination can be deadly, so avoid feeding NPN sources and soybeans together. This includes soybean stubble and NPN sources offered or fed jointly.

Signs of toxicity include excessive salivation, rapid breathing, tremors, tetany, and eventually death. Drenching with a gallon of vinegar may be useful if signs are detected early to neutralize the ammonia and prevent more from absorbing into the bloodstream. Consult with a veterinarian on the best course of action for treating affected cattle.

Urea works best with high-energy diets that contain crude protein levels below 12 percent. When using poor-quality forages, cattle performance can be reduced if urea is used in place of a higher-quality protein supplement such as soybean meal or cottonseed meal. This is likely the result of insufficient UIP in the diet rather than the faster rate of ammonia release in the rumen. Even slow-release forms of urea (biuret) are usually not effective in improving urea use on forage-based diets because of nitrogen recycling of the rumen and liver for secretion in the saliva. Thus, urea is generally a poor supplemental nitrogen source on forage-based diets. This includes forage and grain combination diets commonly used as “step up” rations during the introductory stages of cattle finishing. There is a need for rumen degradable protein other than NPN on these diets.

Rumen bacteria must have sufficient carbohydrate levels (energy sources) available to them if the nitrogen in urea is to be used effectively. Urea generally works best with high-grain diets that are rapidly fermented in the rumen. Forage-based diets are digested too slowly for urea to be used efficiently. In grain-based diets, urea feeding levels should not exceed 0.25 pound per day (no more than 1 percent of the diet). With such small quantities, it is often difficult or impossible to effectively mix urea into mixed feeds on the ranch. Precise mixing equipment is required to do this properly. The best option usually is to purchase a urea-containing supplement from a reputable feed supplier. Never topdress urea over feed offered to cattle.

Lightweight, young calves less than 400 pounds or 120 days old should not be fed urea. Cattle that are large enough and old enough to consume urea should be managed on feed for a few days before adding urea to the diet. Do not feed urea to newly received cattle that have been off feed for a few days.

Nonprotein Nitrogen (Urea) Feeding Checklist

- Closely read all feed tags, checking for urea content in range cubes, protein blocks, and liquid supplements.

- Always weigh urea accurately, and mix feeds thoroughly with proper equipment.

- Feed only in combination with sufficient readily available energy sources, such as feed grains. Do not feed urea on poor-quality forage diets.

- Feed no more than 0.25 pound of urea per day (1 percent of the diet).

- Never feed to calves under 400 pounds or 120 days of age.

- Avoid offering urea to starving cattle or newly received calves.

- Never feed urea and raw soybeans together.

Summary

Protein supplementation often accounts for a large proportion of supplemental feed costs. Several types of supplemental protein sources are available for beef cattle diets. Young, growing cattle and lactating cows are classes of cattle most likely to require protein supplementation. Prices, forms, and protein content of these supplements vary widely. Purchase protein supplements based on price per unit of protein. Some protein supplements contain nonprotein nitrogen (urea). Use caution when feeding urea-based supplements. There are several situations where NPN use is not appropriate, including with low-quality forage diets and when feeding lightweight calves. For more information on protein in beef cattle diets, contact your local MSU Extension office.

References

Ball, D. M., C. S. Hoveland, & G. D. Lacefield. 2007. Southern Forages. 4th ed. Potash and Phosphate Institute and Foundation for Agronomic Research. Norcross, GA.

Moore, J. E. & W. E. Kunkle. 1995. Improving forage supplementation programs for beef cattle. Proc. Florida Ruminant Nutr. Symposium. Univ. of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

National Research Council. 2000. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. 7th Revised Edition, 1996: Update 2000. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C.

Rossi, J. & R. Silcox. 2007. Protein Supplements for Cattle. Bulletin 1322. The Univ. of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Athens, GA.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 2499 (POD-09-22)

Reviewed by Brandi Karisch, PhD, Associate Extension/Research Professor, Animal and Dairy Science. Written by Jane A. Parish, PhD, Professor and Head, North Mississippi Research and Extension Center; and Justin D. Rhinehart, PhD, former Assistant Extension Professor, Animal and Dairy Science.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.