Oak Regeneration for the Future

Oaks represent different things to different people. Whether they are hunters, professional foresters, wildlife biologists, conservationists, landowners, or people who simply enjoy the outdoors, oaks are often the most desirable species group in forest management efforts.

Oak wood is often used for furniture, barrels, construction lumber, flooring, and railroad ties, and in the past, it was used for building ships. Tannins found in oak bark are used in leather preparation. Native Americans made a type of flour from ground acorns, and acorns are also an excellent source of food for many wildlife species.

In Mississippi, various red and white oak species are found on both bottomland and upland sites. The value of wood from different oak species varies considerably, with cherrybark oak historically being the premier species. Wood quality varies by species but is also dependent on site characteristics that affect both growth and form characteristics.

The processes and conditions necessary for successful oak regeneration are often not understood. To be considered a successfully regenerated oak stand, you should have at least 400 seedlings per acre at the end of age 1.

Artificial Regeneration

Like most hardwood species, oaks can be artificially regenerated using seedlings. The type of seedlings can vary from 1-year-old bare-root stock to older seedlings grown in large containers. Oak survival and growth depends on a number of factors:

- correctly matching the species to the site

- appropriate site preparation

- effective control of competing vegetation

- quality of seedlings

- proper storage, handling, and planting

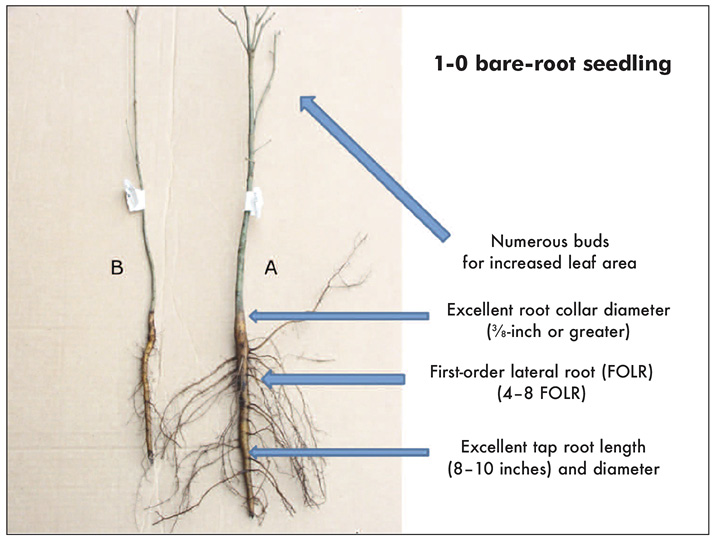

Seedling quality plays a critical role in growth and survival and can greatly affect the time frame for planting. Seedlings should have a minimum root collar diameter of three-eighths of an inch, four to eight first-order lateral roots (these are large diameter roots that extend from the taproot), an 8- to 10-inch taproot, and an 18- to 24-inch branched top (Figure 1). Branched tops will have more leaf buds than a single stem and possess greater leaf area when foliated. Seedlings with this type of top will have greater leaf area for photosynthesis, which is good for early growth. Grade seedlings before going to the field to make sure you plant only high-quality oak seedlings.

As with all hardwood species, correctly matching species to the site is extremely important to ensure survival and adequate growth. All oak species will perform well on soils that are fertile and have good moisture availability year-round. Unique or extreme sites (e.g., sites that are poorly drained, are extremely dry, or have high pH) require specific species (Table 1). For more information on species/site relationships, refer to Mississippi State University Extension Publication 2873 Herbicide Options for Hardwood Management.

|

Soil/Site Types |

Oak Species |

|---|---|

|

saturated – good fertility |

overcup oak, Nuttall oak, willow oak |

|

moist – high fertility |

cherrybark oak, Shumard oak, white oak, swamp chestnut oak, northern red oak (upland sites) |

|

moist – medium fertility |

cherrybark oak, Shumard oak, willow oak, water oak |

|

somewhat dry – medium fertility |

southern red oak, white oak, Shumard oak |

|

dry – low fertility |

post oak, blackjack oak, and scarlet oak |

|

Special Consideration |

|

|

high pH soils |

Shumard oak and overcup oak |

Site preparation can be extremely intensive for hardwoods as most artificial oak regeneration is done on old field sites. Unlike pine species, oaks do not have to have unrestricted access to light and may not need traditional chemical site preparation. If noxious species are not present, chemical site preparation may not be warranted and managers should consider a herbaceous weed control application before planted seedlings break dormancy after planting. If chemical site preparation is deemed necessary, applications should be performed at least 6 months prior to planting to eliminate undesirable vegetative competition from perennial grasses, weeds, vines, or unwanted trees. For more information on appropriate herbicide use in hardwood plantings, please read MSU Extension Publication 2004 Bottomland Hardwood Management: Species/Site Relationships.

Retired fields often have traffic pans (compacted sub-surface layers) created by the passage of equipment over time. Subsoiling is one of the most economical and effective techniques to increase seedling survival and growth. This technique breaks up traffic pans that may restrict root growth. Subsoil on the contour to lower the possibility of erosion.

Unlike pines and some other hardwood species, competition control during the early stages of an oak planting is less critical because oaks can grow through substantial competition. In addition, Oust XP (active ingredient: sulfometuron methyl) can be applied over the top of dormant planted oak seedlings. In most cases, you can apply 2 ounces of Oust XP directly over the top of oak seedlings before bud break.

How many seedlings should you plant per acre?

Some conservation programs require a spacing of 12 feet by 12 feet or 303 trees per acre. This spacing often leads to trees with large-diameter branches that are retained for many years, which in turn causes poor overall stem form due to insufficient woody competition.

Although oaks can be planted at a variety of spacings, the closer seedlings are planted, the better the form and early pruning characteristics tend to be. However, if survival is very high, trees are likely to need pre-commercial thinning to allow them to continue to grow at an acceptable rate. Research suggests that a mixture of oaks with other species such as boxelder, river birch, and sweetgum provide the woody competition necessary to keep oak limbs smaller and help in the natural pruning process. While this argument does have merit, it is difficult and expensive to plant mixtures of species; however, if light-seeded hardwood species do invade oak plantations, it may be beneficial to allow these species to grow together.

Even with quality seedlings, an ideal planting site, and competition control, height growth through age 3 will typically be slow as the seedlings are establishing an extensive root system during this time. The rate of height growth between ages 5 and 10 will increase and average 4–5 feet per year. Height growth will begin to slow after age 10 or as trees begin competing with each other for light, nutrients, and water.

Mortality from suppression is rather low at this time but increases between ages 15 and 20; therefore, in a perfect world with marketable stems, a thinning should take place between 10 and 15 years. Unfortunately, the small size of the material will probably not be acceptable for pulpwood. If a market is not available, the best option is to thin using herbicides through injection.

No matter how this first thinning is performed, it is important to make sure that the best crop trees are not harvested because they will be your future source of revenue. At this age, favorable traits are straight stems, small branches, early pruning, and lack of forking.

Natural Regeneration

Due to the high cost of artificial regeneration and the extended period of time until harvest, hardwoods have typically been regenerated naturally. To help ensure successful natural regeneration, you must address these questions:

- What is the condition of the present stand?

- Are there sufficient numbers of desirable oak species in the present stand to form the next stand?

These questions are often not addressed, and the stand is harvested with little thought about the future. The makeup of the future stand is frequently left to chance, which usually results in a stand with reduced quality and value.

The regenerative capacity of the stand must be assessed. Either a sufficient number of healthy upper canopy oaks capable of serving as seed sources or a sufficient number of seedlings should be present. If there are fewer than 400 oak stems per acre, you will need to either accept this level of oak component, wait on additional regeneration to establish naturally, or use artificial regeneration to increase the oak component. If there are greater than 400 stems per acre, you can cut the stand and allow it to regenerate naturally.

If adequate numbers of oaks are present in the main canopy but very little advance oak regeneration is present, take steps to increase these numbers. The term “advance regeneration” means the seedlings of the desired species are present and have been actively growing for two or three years before the overstory is removed.

Oaks do not regenerate in full shade; thus, it may be necessary to control midstory vegetation so that sunlight reaches the forest floor. Elimination of the midstory can be done mechanically or chemically. The decision depends primarily on the size and extent of the vegetation to be removed. Once this material is removed, you might need to remove some overstory trees, especially non-oak competitors.

When the midstory is removed, it is likely that acorn germination will increase, resulting in a large number of advance regeneration seedlings that will become a part of the future stand. The overstory can be removed when seedling numbers are sufficient. Although some seedlings will be damaged during the removal of remaining trees, their root systems will allow them to resprout. Stumps from the harvested trees may also sprout, providing an additional oak component.

The growth of a naturally regenerated stand is typically slower than that of a correctly established artificially regenerated stand. This is because naturally regenerated oak seedlings endure more intense vegetative competition and have to establish root systems. Where sufficient numbers of seedlings exist before the overstory is removed, the future stand should have a strong oak component. Yet, it will take time for these seedlings to grow through herbaceous and woody competition.

In cases where there is not a strong oak component in the overstory, planting correctly matched oak species is a way to increase the number of oaks on a per-acre basis. This combination of artificial and natural regeneration has been termed “enrichment planting.” The seedlings planted could be small, 1-year-old bareroot seedlings or larger container-grown trees. In areas that receive periodic flooding, use larger seedlings that will not be covered completely by water during portions of the growing season.

Conclusion

Oaks can be regenerated artificially or naturally. Artificial regeneration is best for land that was previously in pasture, agriculture, or forest stands with insufficient numbers of desirable stems. In this situation, subsoiling is likely needed to break up traffic pans. Subsoiling provides an excellent planting area and maintains moisture availability during the summer.

Natural regeneration is more economical; however, you must take steps to ensure a high oak component in the next stand. You must remove the midstory to allow for advance regeneration of the oak component. Once sufficient oak advance regeneration has formed, you may remove the overstory component.

In either case, the ability of the forester or landowner to manipulate the conditions for oak regeneration will determine the quality of the future stand and the revenue it produces.

References

Self, A. B. (2023). Artificial regeneration of bottomland hardwoods (Publication 3486). Mississippi State University Extension Service.

Self, A. B. (2023). Bottomland hardwoods: Natural regeneration using the shelterwood system (Publication 3461). MSU Extension Service.

Self, A. B. (2020). Bottomland hardwood management: Species/site relationships (Publication 2004). MSU Extension Service.

Self, A. B., & Ezell, A. (2020). Herbicide options for hardwood management (Publication 2873). MSU Extension Service.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 2625 (POD-03-25)

Revised by Brady Self, PhD, Extension Professor, Forestry, from an earlier version by Randall J. Rousseau, PhD, Extension/Research Professor Emeritus, Forestry.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.