How Much Water Does Your Evaporative Cooling System Need?

Mitigating heat stress in poultry production is a challenge. Tunnel ventilation with evaporative cooling has been used for many years to improve thermal comfort and production efficiency. Increasing ventilation rate (cfm) generally increases air speed (ft/min) and the “wind chill effect,” which has been shown to improve performance in broilers, broiler breeders, and layers. As ventilation rate increases, so does the amount of evaporative pad required and the quantity of water used for evaporative cooling (EC). As water is evaporated and bled off, water must be replenished into the system to “make up” the water consumed. The typical water supply design is based on make-up water needs plus bird consumption. Significant drought conditions have occurred in broiler-producing regions of the U.S. in recent years, and, as a result, availability and cost of water are an increasing concern for broiler producers.

EC pad systems are sized to accommodate the total building ventilation rate (cfm) while maintaining appropriate air speeds entering the pads and minimizing increases in static pressure. Typical design velocity for the air entering pads is usually around 350 ft/min, but actual velocity at the pads may range from 150 to 600 ft/min or more depending on length of pad, ventilation capacity, and where the measurement is taken along the pad length. The length of pad installed on each side of the house is affected by house width (cross-sectional area) as well as desired house wind speed. As house width increases from 40 feet to 60-plus feet, more ventilation capacity and more pads are required to maintain 350 ft/min across the pad. The increased pad evaporates more water and requires more make-up water. For Meridian, Mississippi, a 40-foot-wide house with 700 fpm windspeed will need 11.2 gpm of make-up water to offset evaporative loss, whereas a 60-foot-wide house would use 16.8 gpm; a 50 percent increase.

Climate and weather patterns vary significantly over the geographic range where commercial poultry houses are located and result in varying make-up water needs for the EC systems. A “one size fits all” recommendation for make-up water needs may result in improperly sized water supply piping, which can lead to insufficient water supply during periods of increased demand. The goal of this publication is to provide information on how much peak evaporative make-up water is needed for typical 6-inch pad configurations.

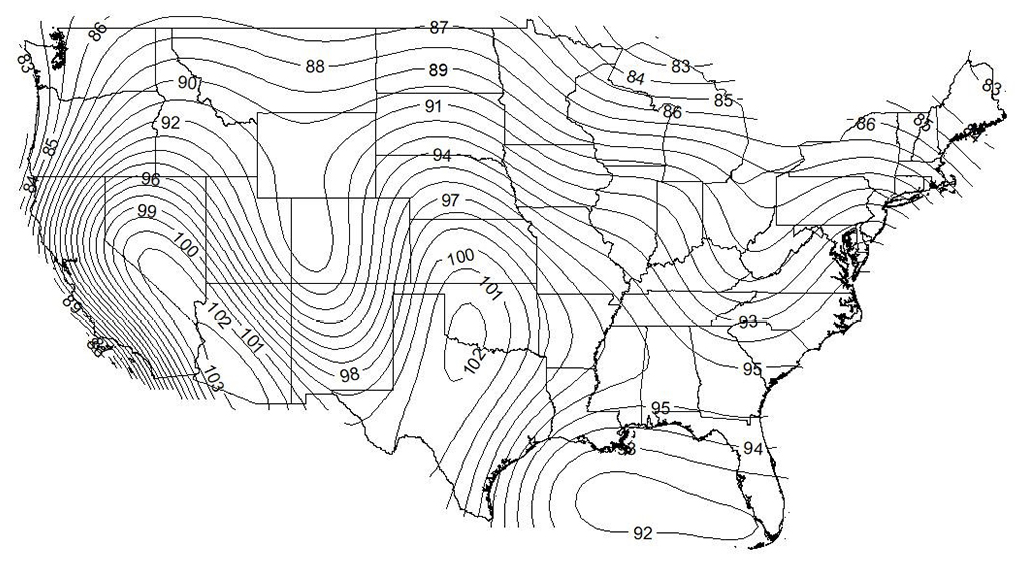

Design or extreme temperatures, rather than average temperatures, are used to determine the amount of cooling required for a poultry house. Design temperatures are classified as 2 percent, 1 percent, and 0.4 percent, which refers to the number of hours that exceed those temperatures in a year. For example, the most extreme category (0.4 percent) for Meridian, Mississippi, is 96.8°F, which means that temperatures exceeding 96.8°F will occur for only 35 hours each year (8,760 hours/year × 0.004 = 35 hours). Extreme temperature contour data (0.4 percent) for the continental U.S. is shown in Figure 2; note that extreme temperatures for much of the “broiler belt” are well below 100°F.

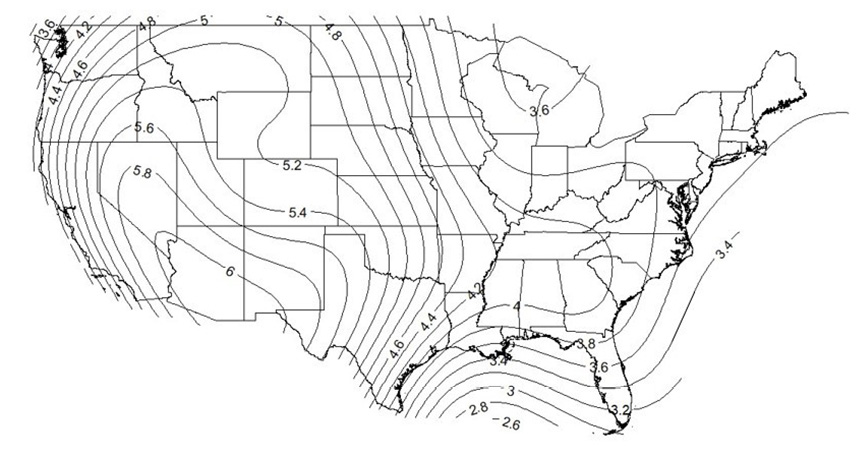

Figure 3 represents the peak evaporative make-up water needs expected for a 6-inch pad system operating continuously in the hottest of weather design conditions. Make-up water requirements are presented as flow rate (gpm) of water per 100,000 cfm of airflow during tunnel ventilation. Values from the maps can be scaled up or down with ventilation rate to predict changes in consumption rates with changes in system size or operation. The examples below show make-up water needs for houses of varying width (40, 50, and 60 feet) and at different geographic locations. As the houses get wider, the average desired windspeed (700 fpm for our example) must be maintained over a larger cross-sectional area. This leads to more required ventilation capacity (cfms) that requires more make-up water (gpm). Due to a lower humidity climate, our example houses below would evaporate 30 percent more water in Livingston, California, than Meridian, Mississippi (14.6 versus 11.2 gpm, respectively).

The make-up water rates in Figure 3 and the examples below do not include continuous bleed-off that is recommended to flush the buildup of minerals and other contaminants in the EC system. If you have a program or your system is set to continuously bleed off, you should add that flow rate to the evaporative rates to obtain your total system make-up needs.

Note: If your farm is located between two of the contour lines, round up to the higher of the two contour lines. In the examples below, Laurel, DE, falls between the 3.6 gpm contour line and the 3.8, so it is best to be on the safe side and round up to 3.8.

Example calculations using Figure 3

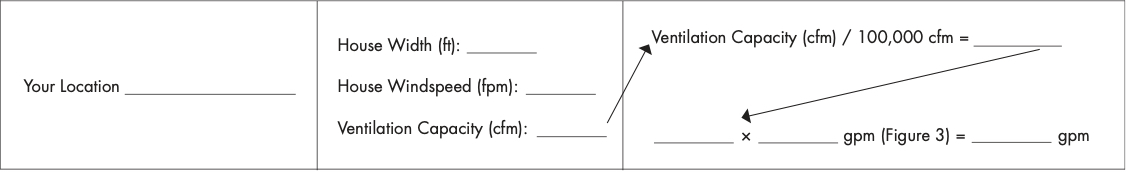

make-up water (gpm) = [(tunnel ventilation capacity (cfm) / (100,000 cfm)] × value from Figure 3 nearest your location (gpm)

ventilation capacity (cfm) = house width (ft) × [(peak height (ft) + sidewall height (ft)] / 2) × house windspeed (fpm)

|

Location |

House Specifications |

Make-up Water Needed |

|---|---|---|

|

Meridian, MS |

House Width: 40 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 280,000 cfm |

(280,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 2.8 2.8 × 4 gpm* = 11.2 gpm |

|

Meridian, MS |

House Width: 50 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 350,000 cfm |

(350,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 3.5 3.5 × 4 gpm* = 14 gpm |

|

Meridian, MS |

House Width: 60 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 420,000 cfm |

(420,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 4.2 4.2 × 4 gpm* = 16.8 gpm |

|

Laurel, DE |

House Width: 40 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 280,000 cfm |

(280,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 2.8 2.8 × 3.8 gpm* = 10.6 gpm |

|

Laurel, DE |

House Width: 50 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 350,000 cfm |

(350,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 3.5 3.5 × 3.8 gpm* = 13.3 gpm |

|

Laurel, DE |

House Width: 60 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 420,000 cfm |

(420,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 4.2 4.2 × 3.8 gpm* = 16.0 gpm |

|

Livingston, CA |

House Width: 40 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 280,000 cfm |

(280,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 2.8 2.8 × 5.2 gpm* = 14.6 gpm |

|

Livingston, CA |

House Width: 50 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 350,000 cfm |

(350,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 3.5 3.5 × 5.2 gpm* = 18.2 gpm |

|

Livingston, CA |

House Width: 60 ft House Windspeed: 700 fpm Ventilation Capacity: 420,000 cfm |

(420,000 cfm) / (100,000 cfm) = 4.2 4.2 × 5.2 gpm* = 21.8 gpm |

*These values are from Figure 3 for each geographical location.

Now, estimate your make-up water needs by filling in the information below.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 3329 (POD-11-23)

Reviewed by Jessica Drewry, PhD, Assistant Professor, Agricultural and Biological Engineering. Written by John Linhoss, PhD, former Assistant Extension Professor, Agricultural and Biological Engineering; Joseph Purswell, PhD, Research Agricultural Engineer, USDA ARS Poultry Research Unit; Jeremiah Davis, PhD, Director and Associate Professor, National Poultry Technology Center, Auburn University; and Jess Campbell, PhD, Poultry Housing Specialist, National Poultry Technology Center, Auburn University.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.