Facts about Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases at Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge and National Estuarine Research Reserve

Background

Ticks are small, eight-legged animals. Scientists classify them as arachnids, the same class as spiders and mites. Ticks are external parasites that feed exclusively on blood from a variety of hosts such as mammals, birds, and even reptiles. Humans, especially those who work or recreate outdoors, are often bitten by ticks.

Not all ticks are infected with disease agents, although some are. The tick-transmitted diseases include Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (and related spotted fever group bacterial diseases), Ehrlichiosis, Anaplasmosis, Tularemia, Babesiosis, and several viral diseases.

There are approximately 20 species of ticks occurring in Mississippi, but only five of them are significant pests:

- Gulf Coast tick, Amblyomma maculatum

- American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis

- Deer tick, Ixodes scapularis

- Lone Star tick, Amblyomma americanum

- Brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus

Tick Biology

Ticks are divided into two major families—hard ticks and soft ticks. Soft ticks are rare and seldom encountered in the eastern U.S., while hard ticks are fairly common. Hard ticks attach to people or animals for several days while feeding.

Ticks are not evenly distributed in nature, nor are they active at the same time seasonally. For example, the Lone Star tick is found throughout most of Mississippi but is not as common along the coast. The gopher tortoise tick is found only along the coast of Mississippi wherever the gopher tortoise occurs. Seasonally, most tick species are active during the spring and summer, but the deer tick is a wintertime tick active from about October through April.

Several tick species occur at Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge and the Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (GBNWR/NERR), but one is by far the most predominant—the Gulf Coast tick, Amblyomma maculatum. As is the case with other hard ticks, Gulf Coast ticks have three mobile life stages: larvae, nymphs, and adults (Figure 1). Each of the stages is progressively larger, and in each stage, the tick must attain an animal host for a blood meal.

They get on their hosts by crawling up on grass and weeds to “quest” for a passing animal. Adult Gulf Coast ticks generally quest about 8–16 inches above the ground (Figure 2). Ticks do not jump out of trees onto passing hosts.

Animal hosts for the larval and nymphal stages of the Gulf Coast tick include birds and certain wild rodents, such as cotton rats. Adults feed on large animals such as cattle, goats, horses, and deer. At GBNWR/NERR, adult Gulf Coast ticks feed primarily on deer, but they will readily bite people.

Disease Transmission

The Gulf Coast tick is a relatively large species, with very long mouthparts, which produce a painful bite. Some Gulf Coast ticks are infected with Rickettsia parkeri, a spotted fever group bacteria that causes an illness similar to but milder than Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A key characteristic of infection with R. parkeri is a spot of necrosis (dead tissue) on the skin at the place where the tick was attached. The illness is treatable with certain antibiotics, especially if recognized and treated early in the infection.

Both species of dog ticks may transmit the agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, while the Lone Star tick can carry the agents of Ehrlichiosis, Tularemia, and perhaps Heartland virus. The deer tick is a proven vector of Lyme disease in the northern U.S., but case numbers of Lyme disease in Mississippi are low.

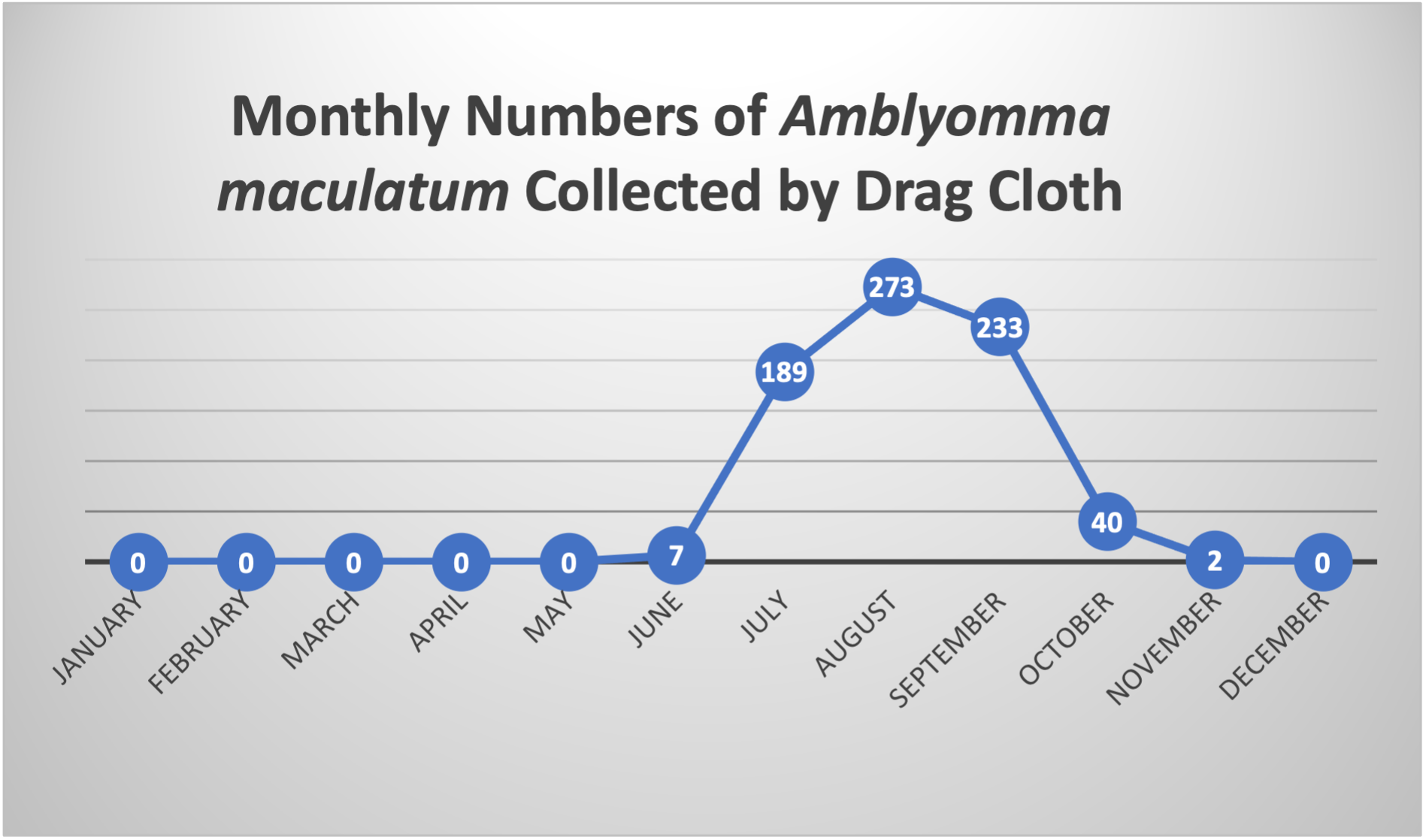

Seasonality of the Gulf Coast Tick

As part of a Mississippi State University Extension Master Naturalist project, the authors collected ticks every two weeks with a drag cloth along the Pine Savannah Trail at GBNWR/NERR. During the year-long project (2022–23), we collected a total of 762 ticks—744 adult Gulf Coast ticks, 14 adult American dog ticks, and four adult deer ticks.

As expected, the deer ticks were collected only in winter or early spring. The dog ticks were collected in June, July, and September. Overall, ticks were rarely collected in the pine savannah until July when Gulf Coast ticks began to emerge.

The peak of activity was early August, when hundreds of Gulf Coast ticks were collected at each visit (Figure 3). During that time, the drag cloth would sometimes have 5–15 specimens on it each time it was turned over for inspection, approximately every 10 yards along the trail. Numbers of Gulf Coast ticks collected began to decrease in late September, but a few specimens were collected as late as early November.

|

Date |

Number Collected |

|---|---|

|

January |

0 |

|

February |

0 |

|

March |

0 |

|

April |

0 |

|

May |

0 |

|

June |

7 |

|

July |

189 |

|

August |

273 |

|

September |

233 |

|

October |

40 |

|

November |

2 |

|

December |

0 |

What to Do about Gulf Coast Ticks at GBNWR

Personal protection from ticks includes avoiding tick-infested woods during peak tick activity, wearing boots with pant legs tucked into them, and using repellents on pant legs, socks, and/or boots (Figure 4). Tucking pant legs into boots forces ticks to crawl up the outside of the pants, making it easier to spot and remove them.

Repellents are somewhat effective against ticks. One study showed that formulations of DEET, IR3535, and picaridin containing at least 20 percent active ingredient were highly effective in repelling Lone Star ticks for 12 hours.

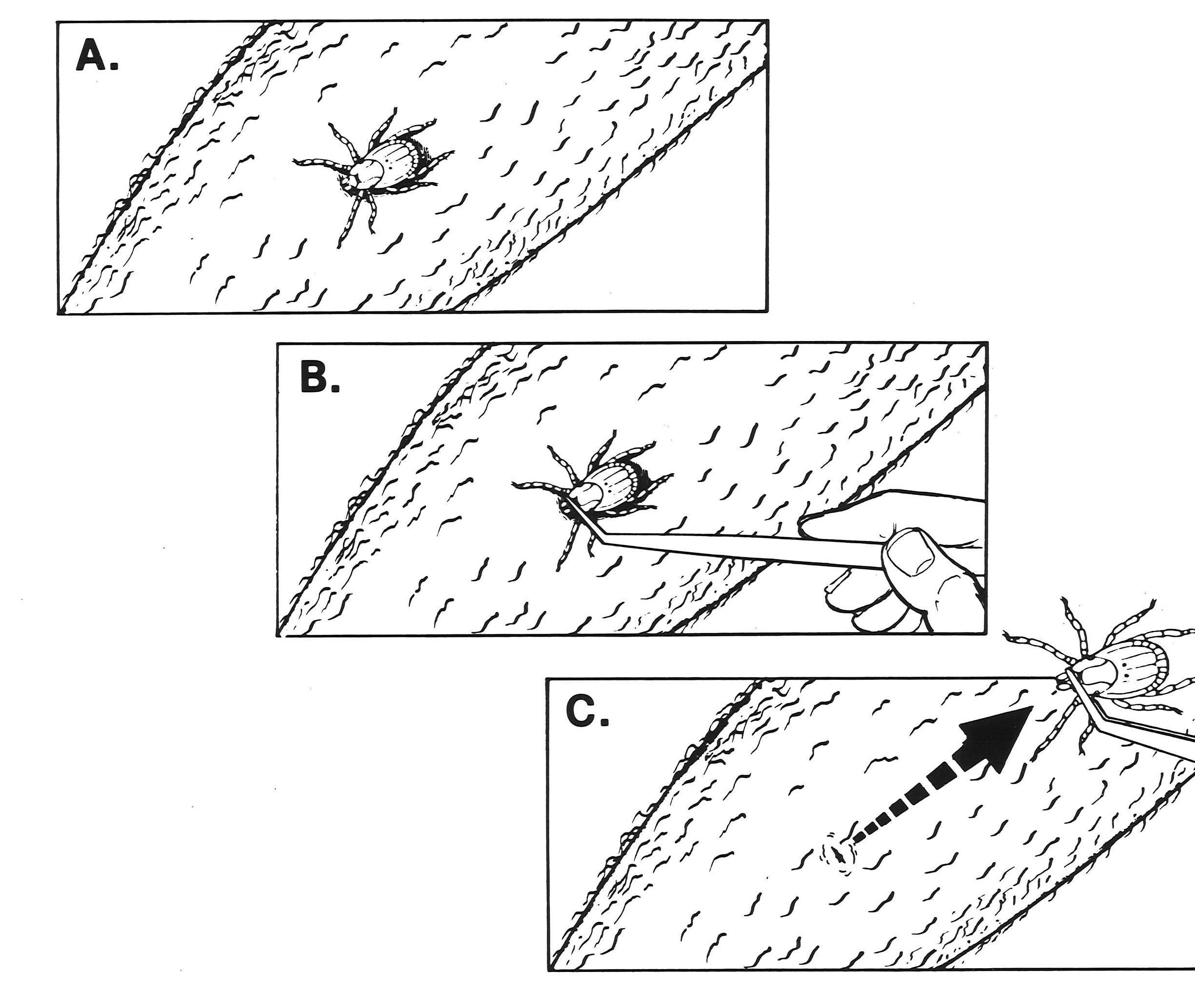

Because the lengthy feeding period is an important factor in the disease potential of ticks, it is important to find and remove attached ticks as soon as possible after being outdoors. That means checking all parts of your body, including around the waistline, groin, back, behind the knees, arms, armpits, neck, ears, and scalp.

If not removed immediately, hard ticks remain attached to a person for several days and may be difficult to remove. Although there are many folk methods for removing attached ticks, the best thing to do is pull them straight off with blunt forceps/tweezers (Figure 5). Any person experiencing unexplained fever, headache, body aches, and/or rash within 2–3 weeks of a tick bite should consult a physician.

Publication 3918 (06-23)

By James Rigney, Master Naturalist, and Jerome Goddard, PhD, Extension Professor of Medical Entomology.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.