Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on October 28, 2021. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

Chronic wasting disease in deer impacts hunters

ASHLAND, Miss. -- The appearance of chronic wasting disease on the Mississippi landscape is making significant changes in the lives and hobbies of hunters, and many are ready to do what it takes to limit this disease.

Chronic wasting disease, or CWD, is a prion disease of white-tailed deer that is easily transmissible to deer through saliva, feces, urine or a contaminated environment. A prion is a type of protein that can trigger normal proteins in the brain to fold abnormally. Prion diseases can affect both humans and animals and are sometimes spread to humans by infected meat.

CWD is fatal to deer in every instance. If left unmanaged, it devastates the deer population. CWD has never been known to transmit to humans.

Arneal Tucker lives and hunts in north Benton County, which has the highest known concentration of CWD cases in the state. Fifty-six of the state’s 83 positives have been reported from this county. Tucker harvested three of these positives.

“I hunt to feed my family. We depend on it for the winter to get by,” Tucker said. “It helps on the cost of the groceries when I have deer in the freezer.”

Tucker harvested four deer over the 2019-2021 deer hunting seasons. When he sent the meat to the processor, he also took the heads to testing sites. Tucker kept the venison separate until the test results came back, but he had to throw away the meat from three of his deer.

“CWD has had a great impact on me because no one expects to take your meat in and pay a lot of money to have it processed, and then when you get it back, you can’t eat it,” Tucker said. “I test every deer I harvest. I won’t take the risk. My family is too important for that.”

Tucker, who has been hunting since he was about 8 years old, hunts on a friend’s land. Nearly all the hunting he has ever done has happened in Benton County, which now has the state’s highest reported incidence of CWD. When he harvests a deer, he shares his bounty with others.

“My immediate family is older people in my neighborhood and such, and they can’t go hunting, so I take it on myself to share what I get,” Tucker said. “They have been calling me and expecting some more meat, but I don’t have any now.”

Wildlife specialists have determined that the best management practices to keep CWD numbers in check are to lower deer density and eliminate practices that encourage deer to congregate.

“This is why the state’s regulatory agency allows more deer to be harvested in CWD zones and why supplemental feeding is eliminated in these areas,” said Bronson Strickland, wildlife specialist with the Mississippi State University Extension Service.

“Supplemental feeding does not cause CWD, but it facilitates its spread as deer concentrate in certain areas, such as around a feeder,” he said.

Jonathan Cooksey is another hunter in north Benton County. His family submitted several deer for testing in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 deer seasons, and three came back positive for CWD. He quit hunting in neighboring Hardeman County, Tennessee, after it became one of that state’s top counties for CWD prevalence.

“We give away the meat after the results come in, but we do not eat it anymore,” Cooksey said.

He has been trophy hunting in the same 4-mile radius his whole life.

“We always ate our venison when we killed a deer,” Cooksey said. “I started for sport and food, then transitioned to more of trophy hunting and deer management.”

When Mississippi first reported CWD and numbers began rising in Tennessee near where he hunts, Cooksey began to entertain the thought that CWD could be on his land, but he did not want to believe it.

“We harvested two nice bucks in the 2019-20 season, and both were positive for CWD. It was a shock,” he said. “Every deer we harvested and tested was positive that year. I test anything I get now.”

William McKinley, deer program coordinator with the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks, said monitoring for the presence of the disease is critical.

“Many areas of the state are not well sampled, so we cannot rule CWD out in those areas,” McKinley said.

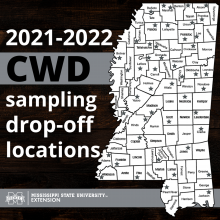

Hunters are encouraged to bring the heads of all deer harvested for free testing at one of 46 drop-off sites across the state. Store the meat in coolers before processing until CWD test results are back, a process that usually takes about a week.

Cooksey said he has noticed an explosion in the deer population where he hunts, and population density is a major contributing factor in the spread of CWD among white-tailed deer.

“Before CWD, you could put out mineral licks and feed your deer and take care of them, but with CWD, we had to stop all that because you don’t want deer congregating,” Cooksey said. “Before, we fed them to keep them healthy; now, we have to do the exact oppositive to keep them healthy.”

Both Tucker and Cooksey said they are willing to participate in efforts to limit the spread of CWD in Mississippi’s white-tailed deer population. They said a quicker test to detect CWD infection would allow hunters to know if meat is safe before they handle it too much and have it processed. Cooksey said he would also like to see more deer harvested each season to keep the population down.

“Maybe we can all get together to work on this problem,” Tucker said. “If there’s a plan to benefit everyone, I’d be more than glad to work with that toward a solution.”

Find more information about CWD and its management and testing at http://mdwfp.com/wildlife-hunting/chronic-wasting-disease. A map shows drop-off locations and times. There is also an app to help hunters with this process.