Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on January 31, 2013. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

Different perspectives result in new solutions

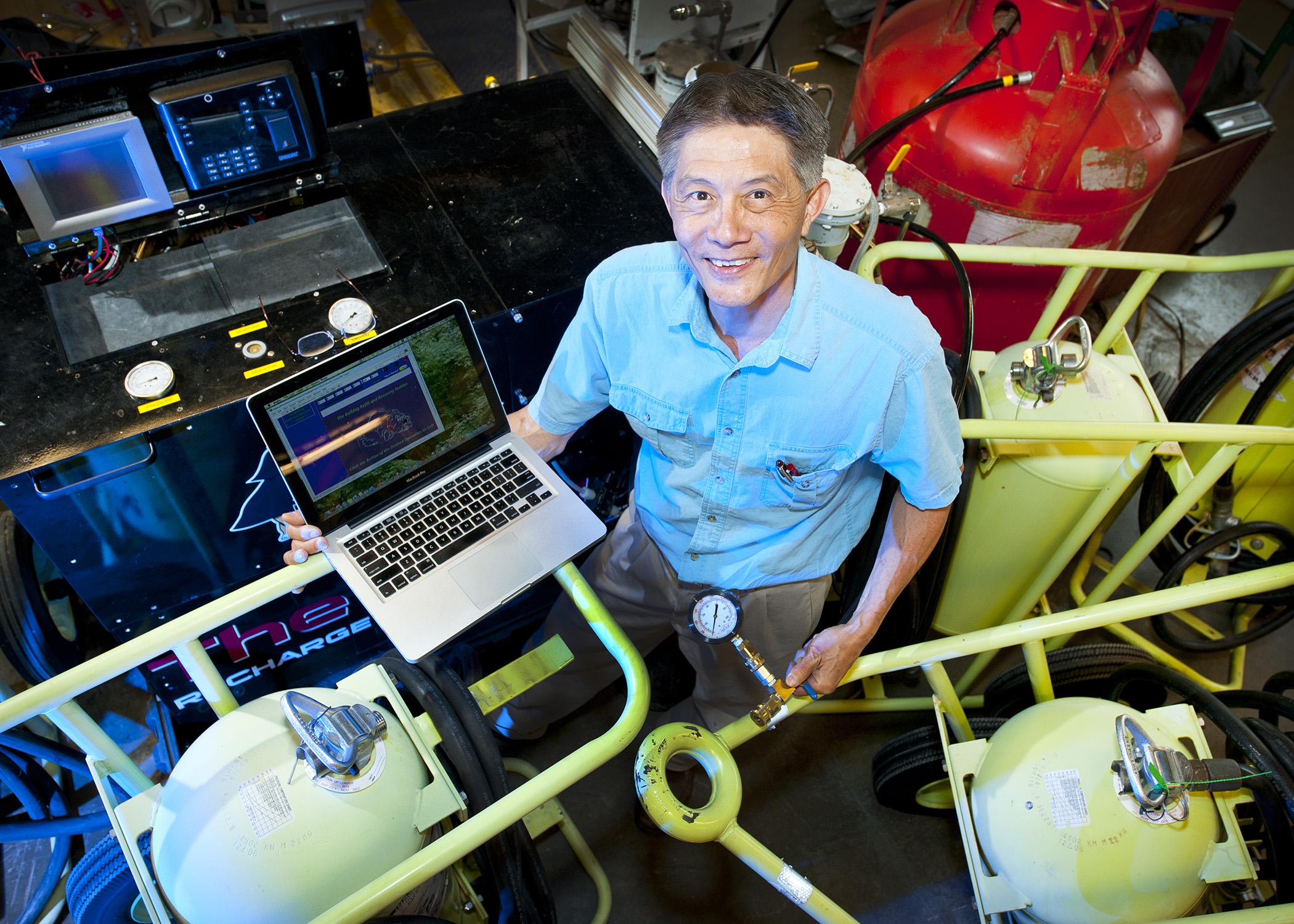

MISSISSIPPI STATE -- Today’s agricultural careers are a long way from the chisels and plows our great-grandparents used, and much of that progress is thanks to people like agricultural engineer Filip To.

To did not begin his career with any sort of agricultural background or education. He grew up in Indonesia and eventually earned his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from Mississippi State University in electrical and computer engineering. His career path took a turn when he became a student worker in the MSU Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. His primary job was to “fix things.”

After graduation, he was hooked on agricultural engineering. For three decades, To has taught and advised students and conducted research to discover better ways to do a multitude of tasks. He is a researcher with the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station.

“I’ve spent a lot of time listening to farmers and observing their work to find out about their challenges and to consider ways to make their work more efficient and productive,” he said.

When To recites a list of some of his projects, it’s easy to see why he is never bored. He has studied heat detectors for dairy cattle reproduction, fire ant mound mapping to improve bait treatments, systems to count catfish fingerlings and dead fish, methods to control rice field flooding, cameras on turkeys to study habitats, ground-based fertilizer applicators, and soil sampling techniques to assess nematode infestations.

Most of his teaching efforts involve electronic instrumentation and engineering design classes. To said robotics or automation can make many agricultural activities more economical and efficient.

“The field of agriculture is wide open. It’s great for people who like to solve problems,” he said. “My lack of a background in agriculture often leads me to different solutions to the problems or challenges.”

In the early 1990s, KBH Corporation of Clarksdale -- which manufactures and sells fertilizer equipment, cotton module builders, cotton carts and other products -- turned to MSU agricultural engineers to create a cost-efficient, automated cotton module builder. Before automation, modules were created manually by a person sitting on the builder.

KBH sales manager Tim Tenhet remembers the day a coworker drove him to see “something special” in a Delta cotton field.

“I was new on the ag scene and didn’t know what to expect when we drove out near Schlater. There, atop a module builder and covered in lint was a grinning Filip To,” Tenhet said. “He had worked with fellow engineer Herb Willcutt to deliver a cost-effective, reliable, automated cotton module builder. For almost 20 years, it was an industry standard.”

Tenhet said he is impressed by To’s happy, positive, can-do attitude.

“Things we see as challenges, he sees as opportunities,” he said. “Creating an affordable, automated module builder was a win for the university, a win for KBH and win for the American farmer.”