Improving Working Relationships between Board Members and Water System Operators

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

— George Bernard Shaw

Board members and operators face increasing challenges in managing and operating successful public water systems in today’s economy. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, employed people ages 25–54 spend an average of 8.8 hours working each day. Because of this large time commitment, the workplace is much more than the four walls of an office, especially if the workload includes late nights and high stress levels, as public water systems often do.

Leading a sustainable public utility takes more than understanding the technical aspects of providing reliable public service; it takes dedication and cooperation between board members and the operators implementing the board’s decisions. To a large degree, a utility should be managed as a business by avoiding favoritism toward customers and earning sufficient revenue to cover expenditures and fund plans for future improvements. Board members and operators are also expected to run a public water system as a public service by showing compassion for customers and satisfying customers’ expectations while protecting a sustainable operation.

Maintaining a balance between business and public service may become more difficult if the board members and operators do not have a supportive working relationship. Obstacles that make an already difficult task more challenging include increasing regulatory scrutiny, failing infrastructure, and an aging and retiring workforce. Many operators and board members face one urgent priority after another, leaving little time for developing communication. Effective working relationships and improved communication techniques establish a positive work environment to improve production and services for the community.

Building a Positive Working Relationship

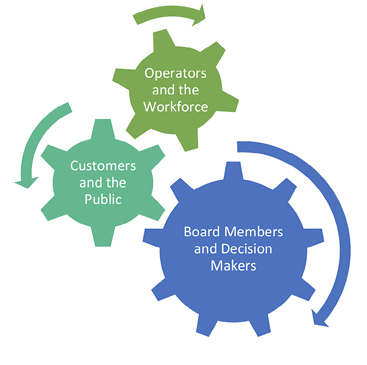

Board members and operators need teamwork and communication to operate any public utility. Board members, operators, and consumers are all focused on the same objective—having access to an affordable and reliable public service for the community. Managers and board members who attempt to build open lines of communication with employees and operators are more likely to develop efficient working relationships, improve job performance from employees, and encourage higher productivity levels. Board members should use diverse communication techniques to interact with employees, inspire improvement, deliver information, request feedback, and motivate employees. Studies examining the effects of open communication on the often-strenuous relationship between employees and management suggest open communication is an effective approach to increase employees’ performance and dedication. Open communication indicates the organization cares about the well being of employees and values employee contributions. When managers communicate openly and welcome employee input, which creates upward and downward lines of communication, employees are more likely to be dedicated and work more effectively for the organization. See Figure 1.

Working as a Team

In order to improve the relationship between operators and board members, communication is needed to understand respective duties and responsibilities. Ask the following questions to ensure all members of the management team agree that the top priority is providing safe drinking water to all customers:

- Who are you serving?

- Are you dedicated to the organization’s mission statement?

- What influences your decisions as a board member or operator?

- How can you measure the success of the organization?

When members of an organization are involved in the decision-making process and encouraged to voice ideas, they have a higher feeling of commitment to the success of the organization. There is a strong link between high-performing organizations and meaningful communication methods. Communication can help achieve concrete changes by encouraging employees to have a vested interest in the outcomes of organization-changing decisions. Various methods of communication offer opportunities for everyone to voice concerns and establish clear and reasonable expectations. Board members and operators should not rely solely on emails or messaging to communicate. People who communicate directly in face-to-face meetings show preparation and dedication to succeed. When communicating in person, simple things such as where a person is seated can affect the atmosphere of the situation. Individuals who sit side-by-side indicate cooperation, while individuals facing one another across a table may indicate competition. In-person meetings encourage those involved to be proactive and take initiative to find solutions to water system issues. However, even the best communication efforts lose their effectiveness when two parties fail to reach a compromise.

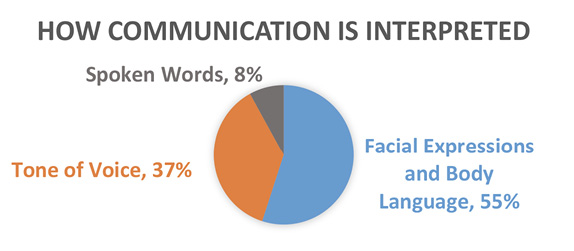

Albert Mehrabian, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, has pioneered the understanding of communications since the 1960s. The statistics in Figure 2 from Mehrabian’s experiments refer to the verbal and nonverbal communication of feelings and attitudes. Often, the situations operators and board members are involved in are the ones they feel passionate about. Although it can be difficult to set aside feelings and emotions when communicating, take into consideration that Mehrabian’s research shows 92 percent of what is remembered from an interaction relies on tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language instead of spoken words. When spoken words do not match facial expressions, people tend to believe the expression they saw rather than the words spoken.

Defining Responsibilites

Maintaining a successful water system requires board members and operators to focus on several influencing factors and responsibilities. See Table 1.

Board members and operators should focus on communicating about and collaborating on those factors everyone is responsible for, especially maintaining public relations and abiding by legal obligations. Also, the specific responsibilities of each party should be recognized and acknowledged. Accountability and recognition is important because it encourages mutual respect and trust.

|

Influencing factors |

Responsibility of |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Board members |

Operators |

|

|

Public image/public relations |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Managing finances |

Yes |

No |

|

Managing/supervising employees |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Legal obligations |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Physical demands and responsibilities of system 24 hours/day |

No |

Yes |

|

Attending educational classes |

Yes (only once) |

Yes (ongoing to maintain license) |

Board Members

As decision-makers for the organization, board members must be approachable leaders who help guide the utility’s direction. Leading by intimidation negatively affects morale and often reduces employee productivity. Board members should establish a supportive line of communication with all system personnel, especially the system operator.

Leadership IQ (www.leadershipiq.com/) conducted a study in December 2009 that revealed the following statistics:

- 65 percent of employees say that when their supervisor criticizes performance, the supervisor doesn’t provide enough useful information to help employees correct the issue.

- 66 percent of employees say they have too little interaction with their supervisor.

- 67 percent of employees say they don’t get enough positive feedback.

If two-thirds of employees are working without receiving appropriate feedback from management, there is a communication crisis in the workplace. A communication crisis may be avoided if the board members provide clear goals and directions for the operator, especially when describing the system’s mission. If an operator does not know where the organization is headed, it is impossible to help the organization get there. Organizations function more effectively if operators can begin with the common goal in mind.

Although operators typically do not make official decisions, it must be acknowledged that the operator knows more about the technical aspects of the system than anyone else involved in the decision-making process. Including operators’ input in the long-term planning process encourages operators to become a valuable source of information for the board. It can be a challenge for information or employee suggestions to consistently reach the top decision-makers in an organization. Board members should designate time at board meetings for the operator to present reports, provide feedback, or offer suggestions to discuss with the board. Open discussion at board meetings can inform operators and other system personnel about upcoming changes or decisions. An experienced operator should be considered the best asset of a water system.

Balancing the financial budgeting required for the water system’s routine maintenance and future improvements is a learned skill. Board members should spend time learning about the water system’s assets and routines from the system’s operator. An experienced operator can offer insight on the daily operation of the system to help board members make financial decisions based on specific system needs. Board members should also spend time with the clerk or office manager to better understand the system’s billing procedures and customer paying habits.

Board members should provide operators with the education and tools necessary to operate the water system successfully. Operators must attend educational classes to satisfy a Mississippi Health Department water operator licensing requirement. Operators are required to obtain a minimum number of continuing education units (CEUs) every 3 years to maintain their water operator license. Board members should encourage educational opportunities beyond the minimum requirement. Additional classes help update the operator on best practices, regulatory changes, and current technology, and allow them to build relationships with other operators.

Board members may employ a general manager or public works director to serve the system and communicate the decisions of the board to the operator and other employees. Board members have one employee in a general manager or public works director. In turn, the general manager may have several employees to oversee, including certified operators, clerks, secretaries, engineers, and others. In this case, board members are legally responsible for the system but are no longer the direct supervisors of the operator, so they should not micromanage operator responsibilities.

Public Water System Operators

Water system operators should provide board members with routine, thorough monthly updates on system needs, repairs, and accomplishments to help board members better understand the condition of the system’s assets. Detailed reports equip board members with up-to-date system information to plan the best path of success for the organization and budget for future improvements. Operators can use monthly board meetings to provide updates to board members regarding the condition of specific assets such as well houses, tanks, meters, and leaks, and any significant interactions with customers. Board members need to be provided with system-relevant information, including positive and negative changes and incidents within the system, to make informed decisions.

Although new board members and city officials are expected to make the utility’s managerial and financial decisions and are held legally responsible for all aspects of the utility, they are often unfamiliar with the daily operations of a public utility. Operators should make an effort to educate board members about the operation of the utility, introduce them to the employees carrying out daily operations, and invite them to attend training classes and conferences. Operators may host a tour of the facility for board members or take pictures throughout the system if board members need to see the condition of the assets. Having board members spend time with the utility and its personnel will help them realize the necessity of rate increases, and it will help them make other financial decisions to maintain the system and continue to provide a safe, reliable public utility.

Conclusion

As the demands on public water systems continue to rise, it is critical that board members and operators focus not only on what decisions are made but also how decisions are reached. Open communication, clear expectations, and a shared vision are required to maintain a successful water system. An honest assessment of the relationships within the system, done with the goal of improving the water system, can be an invaluable use of board members’ and operators’ time. Creating and maintaining strong relationships between board members and operators can pay off in more ways than just good business. When operators and board members improve their working relationships, water systems thrive, board members become engaged, and the community as a whole benefits.

References

Gilley, A., J. Gilley, & H. McMillan. (2009). Organizational change: Motivation, communication, and leadership effectiveness. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 21(4): 75–94.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth (currently distributed by Albert Mehrabian, email: am@kaaj.com).

Ovson, A. (2010). Secrets to giving staff feedback: The threefold path and the feedback success formula. San Francisco, CA: Ovson Communications Group.

Neves, P. & R. Eisenberger (2012). Management communication and employee performance: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Human Performance, 25(5): 452–464.

Sloan, K. (2013). How leaders can create positive attitude.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 2926 (POD-01-21)

Revised by Jason Barrett, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, Water Resources Research Institute, and Kase Kingery, Extension Associate, Extension Center for Government and Community Development. Written by Lauren Behel, former Extension Associate, Agricultural Economics, and William Rutledge, Damage Prevention Coordinator, Mississippi 811 Inc.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.