Melon Aphid/Cotton Aphid, Vol. 8, No. 28

Aphis gossypii

Order: Aphididae

Family: Hemiptera

The fact that this aphid has two “approved” common names, while most insects don’t even have one, says a lot about how important it is. Many species of aphids are pretty host specific, occurring on a relatively few species of plants belonging to a particular family or genus, but melon aphids have hundreds of hosts.

Insects that only have one host, such as boll weevils, are said to be monophagous. Insects that have many hosts are polyphagous. Melon aphids are highly polyphagous, occurring on members of more than one hundred plant families. This means they can cope with an exceptionally wide range of plant defensive compounds and toxins, which helps explain why they can be difficult to control with insecticides.

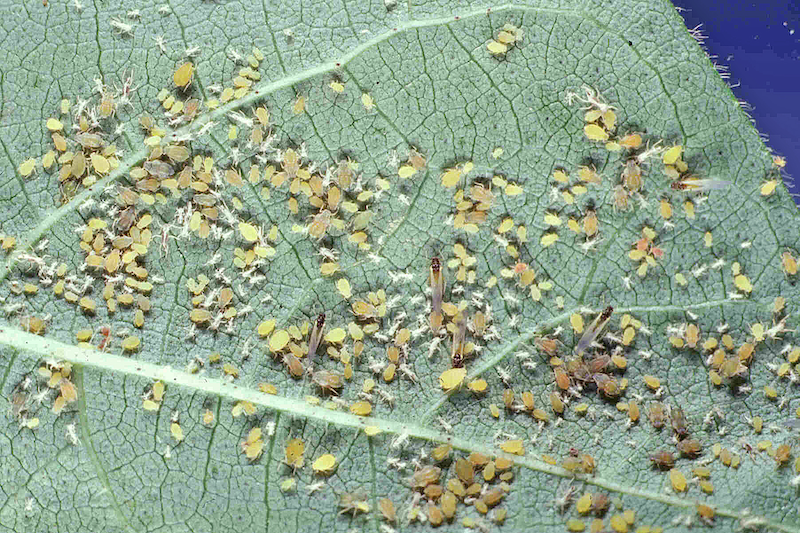

Melon aphids occur worldwide. Here in the US, Aphis gossypii is an important pest on row crops, such as cotton; vegetable crops, such as melons and many others; as well as many ornamental plants. They cause damage by sucking sap through their piercing-sucking mouthparts. Most plants can easily tolerate some sap loss to feeding by low numbers of aphids, but melon aphids can quickly build to high populations, resulting in poor and distorted plant growth and reduced flower and fruit production.

Aphids have some of the shortest generation times in the insect world. Under ideal conditions, like those we have here in the summer, melon aphids can complete a generation in seven to ten days and may have more than 30 generations per year. There are no males. Females reproduce without mating, a process known as parthenogenesis. They don’t lay eggs either. Females give birth to live young, and the nymphs can be grown and giving birth to their own young within seven to ten days.

Cabbage root aphid is an example of an aphid with a much more complicated biology. In some parts of the world, including the northern US, melon aphids do produce males and have a similarly complex life history.

Aphid populations can increase exponentially. If not for natural biological control, our fields and gardens would be overrun with aphids by mid-summer. Fortunately, many biological control agents help suppress aphids. Lacewing, flower fly, and lady beetle larvae eat them; tiny parasitic wasps sting them and deposit eggs in them, and disease organisms infect and kill them. For example, cotton aphids often build to high, yield-threatening populations in Mississippi cotton fields only to be quickly destroyed by an outbreak of an aphid-specific fungal disease, Neozygites fresenii.

Control: In home gardens, both vegetable and ornamental, doing nothing and relying on natural biological control is often effective. However, aphid numbers can balloon quickly if plants are treated for other pests using insecticides that also kill beneficial insects but do not control aphids. Acetamiprid (Ortho Flower, Fruit and Vegetable Insect Killer) is one of the more effective treatments for heavy aphid infestations. The ready-to-use formulation is handy for gardeners who only have two or three backyard eggplant or tomatoes, as well as for controlling aphids and whiteflies on tropical hibiscus. Organic growers can use treatments such as insecticidal soap and neem oil, but spray coverage is more important with these non-systemic, contact-kill products. In large scale commercial greenhouses, aphids are often controlled by repeated releases of parasitic wasps, such as Aphidius colemani, but this is not practical in outdoor or small-scale settings.

Blake Layton, Extension Entomology Specialist, Mississippi State University Extension Service.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. Always read and follow current label directions. Specific commercial products are mentioned as examples only and reference to specific products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended to other prodcts that may also be suitable and appropriately labeled. Mississippi State University is an equal opportunity institution.

Bug’s Eye View is now on Facebook. Join the Bug's Eye View Facebook group here.