Information Possibly Outdated

The information presented on this page was originally released on December 20, 2012. It may not be outdated, but please search our site for more current information. If you plan to quote or reference this information in a publication, please check with the Extension specialist or author before proceeding.

Some careers are ideal for problem solvers

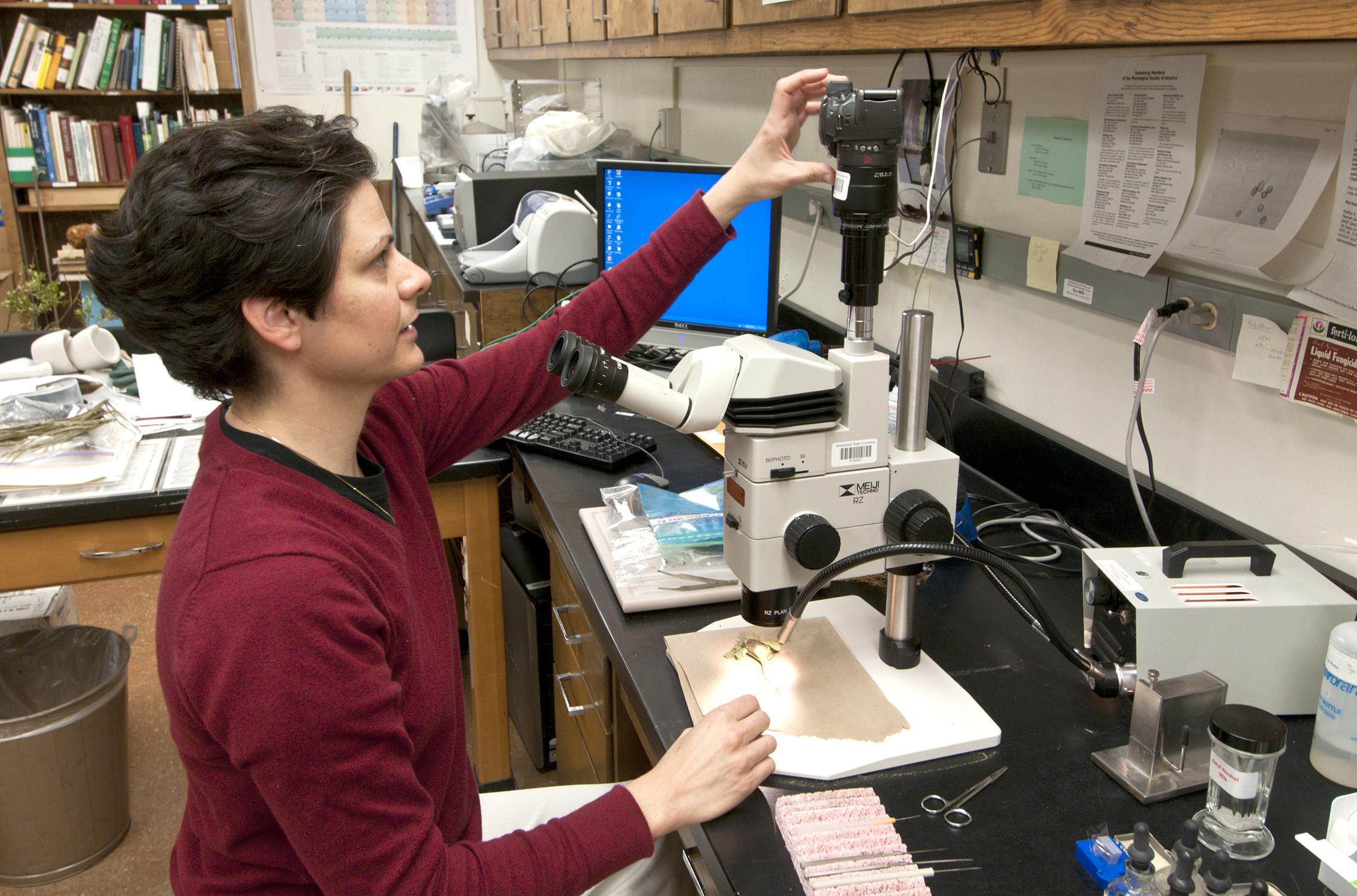

MISSISSIPPI STATE – Clarissa Balbalian’s job presents a new mystery every day.

“If you are analytical and like solving mysteries, this is the perfect job,” said Balbalian, the manager of Mississippi State University’s plant diagnostic lab. “I like working with people and helping them find solutions to their problems, too.”

Balbalian studied biology at Longwood University in Virginia, and then earned her master’s degree in forest pathology at West Virginia University.

“Plant pathology is a great way to be involved in agriculture,” she said. “I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors and been analytical. After considering careers in health-care fields, I decided plant health seemed less stressful.”

Balbalian said the plant-pathology field is wide open with many career opportunities in private industry or government agencies. Pathologists find jobs working domestically and internationally, addressing issues such as food safety and world hunger. Some of the most common opportunities are in academic and state and federal government positions.

“We are approaching a shortage as experienced pathologists retire from agencies such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Forest Service,” she said.

Maria Tomaso-Peterson, associate research professor in MSU’s Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology and Plant Pathology, said it takes a “trained eye” to pinpoint plant problems. She attributed the growing shortage of plant pathologists to a trend toward technical proficiency and away from hands-on abilities.

“Applied pathologists are a dying breed, but what motivates them is the desire to solve puzzles. We are always looking for solutions to make things better,” she said.

Balbalian shared an unusual sample of grass fungus submitted to her lab with Tomaso-Peterson and other researchers. The pathologists were able to identify and document a new disease in centipedegrass. By identifying the fungus that causes centipede anthracnose, pathologists are one important step closer to developing treatments.

“Pathologists first seek to determine what is causing the problem. Sometimes it is a living organism, and sometimes it will be something else, such as a chemical or environmental issue. It helps to have someone with a trained eye to discern disease symptoms from other factors,” Tomaso-Peterson said.

“There is definitely a curiosity aspect behind the work of a plant pathologist,” she said. “That is what Clarissa has -- a lot of curiosity.”