P2832

Thinning Pine Trees by the Leave Tree Method

Although many forestland owners are well aware of the biological need for thinning, at the time of this revision, most are operating in a severe depression of the pine pulpwood market in Mississippi. Because of these poor market conditions, many landowners are waiting for pulpwood values to increase before attempting timber sales. However, we urge landowners to thin when biologically appropriate if possible in spite of the difficulties encountered in today’s markets.

The hope of increased revenue from potential increases in pulpwood value is overwhelmingly outweighed when considering potential economic loss from both slowed timber growth and the chances of insect and disease damage. See Mississippi State University Extension Publication 2732 Protect Your Pine Plantation Investment by Thinning for a detailed discussion regarding the need to thin pine plantations when they reach economic/biological maturity.

At some point after establishment, both natural and planted pine stands in the South need thinning, as tree crowns grow together and trees start to compete with one another. Thinning removes trees of lower quality and/or vigor, increasing overall health and quality of the residual stand.

Images of evenly spaced rows of similarly sized trees come to mind when most people think of pine plantations. However, in reality, many planted stands have a significant number of volunteer stems growing among those that were planted. These additional stems in plantations, as well as the large number often found in natural stands, can create extra challenges when attempting to reduce stand densities to appropriate levels.

While not always the case, current thinning techniques, rules, and systems may be overly complicated for some private landowners. Under actual sale conditions, testing has shown that leave-tree thinning in overstocked pine stands results in a more consistent silvicultural treatment and higher yields per acre than other methods. The relative simplicity of the leave-tree method makes it applicable on private timberlands by nonforesters.

Historically, marking timber was commonplace in management efforts, but it has become uncommon and is typically only used in second or third thinnings in pine silviculture. First thins are typically performed using “operator select” techniques where logging operators select trees to remove based on management objectives. The method is usually very successful if operators are experienced and expectations are clearly outlined. However, some situations still warrant marking, and some landowners are more comfortable knowing that the best trees present are designated and marked to leave as crop trees.

This publication details the method known as “leave-tree marking,” named so because you mark trees that you are going to “leave.” The method is different from the often-used selective-marking technique. With selective marking, the poorest-quality, diseased trees and trees that are undesirable to the goals of ownership are selectively marked to be cut. Leave-tree marking is used in early thinnings to leave the best potential crop trees. The method is especially applicable in young, dense stands where more trees are to be cut than left. After the first or second thinning, you can switch to selective marking because fewer trees will be cut than left. Selective marking is used in these later thinnings to remove poorer-quality trees.

Both methods are used to achieve the same end results—removing poor trees and retaining higher-quality trees. Regardless of which marking technique you use, make sure the method is written into the cutting contract between the landowner and contractor. Additionally, be positive that the logging crew is aware of which marking technique was used. With a little training and experience using the leave-tree method, you can choose the best tree in a small area and leave it marked as a future crop tree.

An additional item to consider when using any thinning method in a first thinning is the issue of access. Overall high densities encountered in both natural stands and plantations dictate removal of “corridors,” or rows of trees, so that equipment may access the remainder of the stand.

In stands that have been naturally regenerated, cutting corridors should be flagged or marked so that logging crews may remove trees within them. Width and direction of corridors will depend on several factors, including size of logging equipment to be used, topography, desired per-acre density of the residual stand, and management goals.

Cutting for equipment access in plantations is a somewhat easier process. Row thinning is used to provide the needed space for logging equipment. The process involves removing entire rows of trees, typically every third or fourth row. This provides access for logging crews to remove unmarked trees from other rows within the plantation.

Whether you are using corridors or removing rows, make sure not to mark leave trees in these areas. Remember, every tree within these areas will be removed. Some of the technical terms used in this publication may be unfamiliar. If you have questions regarding their use, please consult MSU Extension Publication 1250 Forestry Terms for Mississippi Landowners.

Advantages of Leave-Tree Marking

- Nonforesters more easily understand the concept of leave-tree marking.

- It may minimize marking costs because less paint and labor is used to mark leave trees than to mark cut trees in high-density stands.

- It is easier to see the spacing and quality of remaining crop trees before the stand is thinned.

- It typically results in more uniform thinnings.

- Cut marked trees are easy to spot at the loading deck, and stumps marked with paint provide evidence of improper tree removal.

Disadvantages of Leave-Tree Marking

- Logging crews may cut the wrong trees without thorough instruction.

- Marking costs may be greater in second or third thinnings because there will probably be more leave trees than take trees.

How to Measure Tree Diameter

Tree diameter must be used to determine proper tree spacing. Tree diameter is measured at 4½ feet above the ground. Measurements at this height are called diameter at breast height, or DBH. DBH can be measured with a steel diameter tape or a Biltmore stick. The Biltmore stick is quick and easy to use but is not as accurate or consistent as a diameter tape. For information on how to construct or obtain a Biltmore stick and on proper DBH measurement techniques, consult your Extension forestry specialist, or read MSU Extension Publication 1473 4-H Project No. 7: Measuring Standing Sawtimber.

Basic Steps in Leave-Tree Marking

These are the five basic steps to the leave-tree method:

-

Determine the “prevailing diameter” of leave trees in the stand.

- Use the prevailing diameter to select the proper spacing.

- Determine the proper spacing.

- Select and mark leave trees.

- Navigate through the stand.

Determine the Prevailing Diameter

The prevailing diameter is simply the average diameter class of acceptable leave trees most common in the stand of interest. It is not the average diameter in the stand, but rather the average diameter of the trees you want to leave.

Prevailing leave tree DBH can be determined using a tally of selected trees taken at periodic sample points along cruise lines throughout the stand. A cruise line is an imaginary line or path that crosses planted rows or slopes at right angles. Cruise lines are placed so that DBH of acceptable leave trees will be adequately sampled. Plot sampling can also be used, but this is a more complicated process that a consultant would typically use.

Cruise lines should cross planted rows and topographic changes at right angles. The lines should be about 150 feet apart in smaller stands of just a few acres and about 300 feet apart in larger stands. At predetermined distances along cruise lines (for example, every 50 to 100 feet), measure the DBH of the nearest acceptable leave tree. At each sample point, select the nearest dominant or codominant tree acceptable as a leave tree, and record its DBH.

When stand sampling is completed, the diameter class most frequently represented in the tally is the prevailing DBH of leave trees. Tally trees according to their diameter to the nearest inch. Determining proper DBH is important because the prevailing DBH of leave trees is used to select proper spacing.

Use the Spacing Table

It is best to use stand age and site index to select spacing because this will result in complete site utilization for optimum growth and yield. However, if stand age and site index are not known, a reasonable spacing can be obtained using Table 1 for loblolly pine using only prevailing leave-tree DBH.

Table 1 is used to determine how many trees to leave per acre and the desired spacing of leave trees for average-, low-, and high-quality sites. An example of how to use the table is as follows: If prevailing DBH is 8 inches, look within the row for 8-inch trees. In this case, leave trees should be spaced 15 feet apart on low-quality sites, 14 feet apart on average sites, and 13 feet apart on high-quality sites. On average sites, about 222 trees per acre will be left using this spacing. If you are familiar with measuring basal area, an average site “rule-of-thumb” basal area target is the same as site index for the stand. In addition, site quality depends on several factors. If you are unfamiliar with these, a forester, Extension agent, or Extension forestry specialist can help you determine the quality of your site.

Notice across the same row that for a given DBH, more trees per acre are left on higher-quality sites than on those of lower quality. A higher-quality site has more productive soil and can support more trees than a lower-quality site.

Now look at the potential for site productivity (trees per acre) down the same column; fewer leave trees are required per acre for larger diameters than for smaller diameters. As a tree gets larger in diameter, its crown diameter also increases and needs more growing space. Tree spacing controls diameter growth, so if your goal is to produce large sawtimber trees as quickly as possible, you need to thin every 5 to 10 years to optimize increased diameter growth. Remember, the numbers shown here are averages and will vary across the stand. The expectation is not to achieve exact tree spacing or numbers, but to perform a thinning with trees spaced near the spacing values listed in Table 1.

|

DBH (inches) |

Low-quality site BA 70 (trees/acre) |

Spacing (feet) |

Average site BA 80 (trees/acre) |

Spacing (feet) |

High-quality site BA 90 (trees/acre) |

Spacing (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6 |

360 |

11 x 11 |

436 |

10 x 10 |

436 |

10 x 10 |

|

7 |

258 |

13 x 13 |

303 |

12 x 12 |

360 |

11 x 11 |

|

8 |

194 |

15 x 15 |

222 |

14 x 14 |

258 |

13 x 13 |

|

9 |

151 |

17 x 17 |

170 |

16 x 16 |

194 |

15 x 15 |

|

10 |

134 |

18 x 18 |

151 |

17 x 17 |

170 |

16 x 16 |

|

11 |

109 |

20 x 20 |

121 |

19 x 19 |

134 |

18 x 18 |

|

12 |

90 |

22 x 22 |

99 |

21 x 21 |

121 |

19 x 19 |

|

13 |

76 |

24 x 24 |

90 |

22 x 22 |

99 |

21 x 21 |

*Adapted from USDA Forest Service Manual for the Kisatchie National Forest, Louisiana.

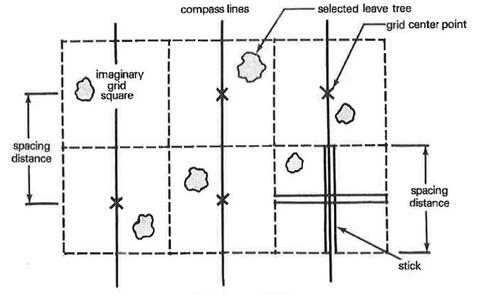

Lay Off the Spacing Grid

For the sake of discussion, assume you have determined a desired spacing of 15 feet in your pine stand. Next, you must divide the stand into a grid of imaginary squares, each measuring 15 feet on each side. It is not necessary to actually mark and/or flag these squares before marking leave trees. The grid system is just a simple way to visualize the method and get you started. A compass will help you walk straight lines and keep squares in their proper locations, but you can use a string as a guide as you gain navigating experience. Aerial photographs and maps can be used to check progress as you move through the stand.

A series of compass lines, 15 feet apart in this instance, will be used to guide you through the stand as you mark leave trees. You may want to tie flagging along your compass lines as you move through the stand. Vinyl flagging provides an easy visual reference point to follow as you travel back and forth through the plantation marking trees.

If you choose to flag your compass lines, make sure that you maintain straight lines by turning around and checking for linear accuracy. Each line will run through the center of a row of imaginary squares. Begin your first compass line half of the spacing distance into the edge of the pine stand (7½ feet in this case). For example, if you begin at the southeast corner of the stand, your first compass line should begin 7½ feet from the south and 7½ feet from the east stand boundaries. This will place you in the center of your first imaginary 15-by-15-foot square. You can use a measuring or logger’s tape to help you judge the size of the square.

Select and Mark the Leave Trees

The purpose of this step is to select the highest-quality tree within the square. Be sure to inspect all trees within the square, including all four corners. Only one tree should be selected, and it can be located anywhere within the square’s boundaries. An acceptable leave tree should be free of disease and relatively straight, and have a well-formed, full crown in the main canopy layer or above the crowns of surrounding trees. Remember, your intent is to leave the best trees and cut those of lower quality. If two or more trees are equally acceptable, select the tree nearest to grid center.

If no “good” tree is present, a less desirable tree (forked, crooked, small, etc.) may be selected rather than leaving the area empty. Again, choose the best tree available in each given square. After selecting the tree you plan to leave, mark it with paint using a large slash at eye level and at ground level on the stump. Consider logging direction, and make eye level marks facing the expected cutting direction. Make sure to use paint generously so that loggers can see the marked leave tree. The stump mark is extremely important because it will serve as the only evidence that the tree was marked in the event of improper cutting. Use a good-quality tree marking paint with lasting power.

Navigate through the Stand

After you have successfully found and marked the leave tree in your first square, use your compass and measuring tape to help you move from center of the first square to center of the next. You can also pace the distance if you are familiar with your pace length. Mark the best tree in that square and keep going. Once you have reached the opposite side of the stand, move over the full spacing distance (15 feet in this example) and start a new line parallel to the first. Continue back and forth until you have covered the entire stand.

You may find it helpful to use two measuring tapes to achieve desired spacing distance. A tape will also help you visualize boundaries of the square. Lay one tape down along your compass line and place the other perpendicular to the first. The crossing point is the center of the square. You can use this method until you have mastered judging the correct distance between square centers and their boundaries. As you gain experience selecting trees and judging proper spacing distance, you will find that you can navigate and mark leave trees very close to the desired spacing, using compass lines and grid squares occasionally as a check.

After Marking Is Complete

Leave-tree marking is not difficult, but, upon completion, you should check your work for large-scale mistakes. Take time to walk back through the stand and observe the spacing of leave trees. The paint marks let you see what the stand will look like after it has been thinned. Now is the time to catch any major errors. Once the stand is thinned, any unchecked mistakes will probably be irreversible. The next time you thin, you may need to use a different color paint to differentiate leave trees from those to be cut if sufficient time has not passed for the original paint to degrade.

The condition of your stand will be much improved after thinning. You have not only increased diameter growth potential of residual trees but have also reduced chances of damage from pine beetles and disease. Additionally, trees that would not have survived until the next logging reentry have been removed, capturing revenue that would have been lost if the stand were left unthinned.

Thinning does have some risks. You might lose a few skinned or damaged trees to various environmental factors. Additionally, there is a greater risk of storm/ice damage in recently thinned stands. However, risk of losing a few trees to thinning is greatly offset considering the much greater health and economic risks involved when leaving a stand unthinned. For more information detailing dangers of leaving pine stands unthinned, see MSU Extension Publication 2732 Protect Your Pine Plantation Investment by Thinning.

If you are uncomfortable marking your pine stand for thinning, consulting foresters can also help on a commission or fee basis. Contact information for consulting foresters can be obtained at www.borf.ms.gov. You can search by county, city, or the forester’s last name. Foresters on this list must be registered with the state, which sets standards for their credentials. For information on selecting a forestry consultant, read MSU Extension Publication 2718 Choosing a Consulting Forester.

For more information and publications about leave-tree marking and other thinning techniques, contact your area Extension forestry specialist or Mississippi Forestry Commission area forester. Mississippi State University Extension also has various publications to help you manage your timber. These can be found at extension.msstate.edu, or you can contact your county MSU Extension agent for more information.

Additional Reading

Brady Self. 2022. Are My Pine Trees Ready To Thin? P2260. Mississippi State University Extension.

James Henderson. 2019. Protect Your Pine Plantation by Thinning. P2732. Mississippi State University Extension.

Brady Self and Shaun Tanger. 2022. Forestry Terms for Mississippi Landowners. P1250. Mississippi State University Extension.

Brady Self. 2023. Choosing a Consulting Forester. P2718. Mississippi State University Extension.

Brady Self. 2022. 4-H Project No. 7: Measuring Standing Sawtimber. P1473. Mississippi State University Extension.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 2832 (POD-11-23)

By A. Brady Self, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, and Robert C. Parker (deceased), Professor, Forestry.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.